A Comprehensive Look at the "Money Empire" Under the Gray Map

Since October, with the booming Bitcoin market, Grayscale has once again become the focus of attention. Labels such as "whale," "compliance," and "Wall Street" have always accompanied it, and many people consider Grayscale to be synonymous with "institutional investors entering the market." Even in the past few weeks, whenever Grayscale traded normally on weekdays, Bitcoin showed an upward trend; while on weekends, Bitcoin experienced declines. Although this phenomenon has a considerable element of coincidence, it does not prevent people from viewing Grayscale as the "savior" of the Bitcoin market.

However, after recently watching "The Wolf of Wall Street," one scene left a deep impression: when the legendary stockbroker played by Leonardo handed a pen to someone nearby and asked them to sell the pen to him, ordinary people would talk about all the advantages of the pen, while his good friend Brad simply said, "Help me out, write your name on this napkin." By creating demand, people are willing to buy stocks, which is a key reason why Leonardo could become the "Wolf of Wall Street."

This brings to mind Grayscale; from a different perspective: if we view Grayscale as a form of artificially created demand rather than a market supply product, we can draw some interesting conclusions.

1. Reassessing the "Value" of Grayscale

Whenever people talk about Grayscale, it is often difficult to understand. This is because it is not like a regular open-end fund; it not only has subscriptions and redemptions but also secondary market trading. The reason is that although Grayscale is called a "trust investment fund," it is essentially a "stripped-down" ETF fund.

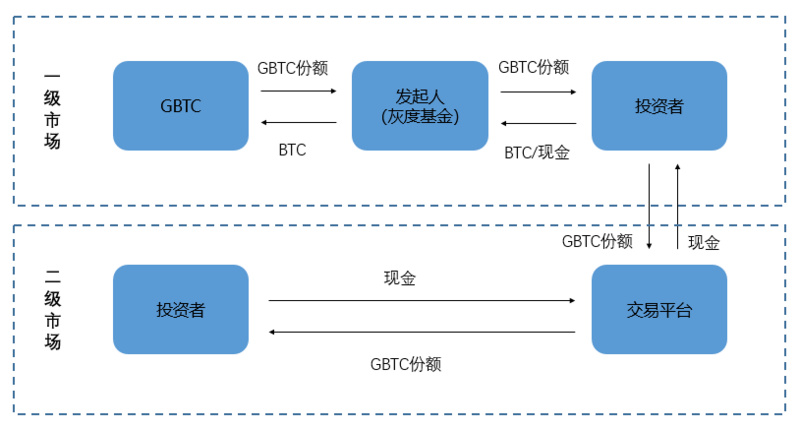

Currently, Grayscale has launched 9 single-asset trust funds (BTC, BCH, ETH, ETC, ZEN, LTC, XLM, XRP, ZEC). Taking the GBTC fund as an example, like all ETF funds, GBTC is divided into two major markets:

The primary market is the issuance market, where investors can purchase GBTC shares using BTC or cash; correspondingly, investors can also exchange GBTC shares for BTC in the primary market, and the GBTC shares will be immediately canceled;

The secondary market is the trading market, where investors can trade their GBTC shares on the secondary market, with the trading platform being OTCQX, which uses a price inquiry trading system.

However, GBTC differs from traditional ETF funds in two ways:

First, since October 28, 2014, the Grayscale Bitcoin Trust has suspended its redemption mechanism. Although GBTC has now passed regulatory scrutiny, it still has not submitted a redemption plan to the SEC.

Second, in traditional ETF trading, T+0 trading can be achieved between the primary and secondary markets, meaning that ETF shares purchased in the primary market can be sold in the secondary market on the same day; a basket of stocks redeemed through an ETF can also be sold in the secondary market on the same day. However, currently, GBTC shares purchased in the primary market can only be sold in the secondary market after 6 months.

Of course, we should also pay attention to the secondary trading market of GBTC—OTCQX.

Whenever investors mention Grayscale, they cannot help but label it as "high-end," partly because all the funds under Grayscale can be traded on the U.S. securities market.

After nearly 200 years of development, the U.S. securities market has formed a multi-tiered capital market system. Based on the quality of company stocks and the degree of market openness, the U.S. capital market system is mainly divided into the following tiers:

The first tier includes the New York Stock Exchange, Nasdaq Global Select Market, and Nasdaq Capital Market, which have high listing standards and mainly cater to super multinational corporations.

The second tier includes the Nasdaq Small Cap Market and the National Stock Exchange, which mainly cater to high-tech companies and small to medium-sized enterprises in the U.S., with lower listing requirements that can meet the listing needs of innovative companies characterized by high risk and high growth. Most of China's internet companies are listed in this market.

The third tier consists of regional securities markets in the U.S., such as the Cincinnati Stock Exchange and the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, which mainly trade local company securities.

The fourth tier is the Pink Sheets market, and OTCQX belongs to this market.

So, what is the Pink Sheets market?

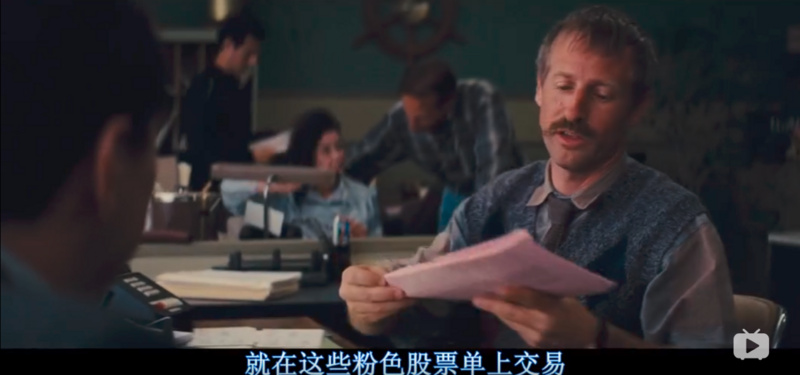

In the movie "The Wolf of Wall Street," there is a scene where Leonardo becomes unemployed after the 1987 stock market crash and has to work as a stockbroker at an "investor center." However, this "investment center" mainly conducts business in the Pink Sheets market (in the movie, we can see stock quotes printed on pink sheets).

It is important to emphasize that the U.S. Pink Sheets market is not a securities exchange. Companies trading on the U.S. Pink Sheets do not have to meet any requirements, such as submitting financial reports to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (which is why we see that apart from the SEC-approved GBTC and ETHE products, Grayscale's other trust fund products can still be traded on OTCQX without submitting reports to the SEC). The companies traded in the Pink Sheets market are often small companies with few shareholders, generally small in scale, with low earnings, or even bankrupt companies, so most of these companies do not meet the basic listing requirements of U.S. trading institutions like the New York Stock Exchange.

Therefore, although there are some high-quality overseas company stocks (mainly depositary receipts) in this market, the vast majority are "junk stocks" and "penny stocks" from the U.S. For example, the "cutting-edge technology company" stock that Leonardo promotes to clients as "soon to receive radar detector approval" is actually just a "family company" in a small, shabby white house in the Midwest. Yet, if Leonardo can successfully sell these stocks, he can earn a 50% commission.

Of course, although the Pink Sheets market is synonymous with "junk stocks" and "penny stocks," it also has market tiers, ranked from high to low as OTC QX, OTC QB, and OTC Pink. Grayscale belongs to the OTCQX trading platform.

OTCQX is the highest tier of the U.S. over-the-counter trading market, and all companies trading here must meet standards for information disclosure, financials, and management (these standards are not set by the SEC but by the trading platform), and must provide proof of support from certified third-party investment banks or legal advisors.

Therefore, in practical terms, Grayscale is merely a "stripped-down" ETF fund, and its trading platform is just a "third-rate platform" in the U.S. financial market system, with low intrinsic value.

2. The "Money Empire" Under Grayscale's Domain

Through the above analysis, we may wonder, since the products under Grayscale have low "intrinsic value," why do so many investors flock to it?

Many might explain this with the misleading phrases on Grayscale's official website, such as "convenient and secure," "cost-effective order execution." Since small and medium investors can buy and store cryptocurrencies themselves, do institutional investors not do the same? Are institutional investors focused on "compliance channels"? Clearly not, because CME has already launched "BTC futures," and is there a significant difference between leveraged BTC futures and BTC spot? Perhaps the trading fees for rolling over the former are cheaper than Grayscale's management fees, and they can also magnify leverage and save on capital costs.

Perhaps for those paying attention to Grayscale, the starting point for analyzing the issue may be wrong—public narrative logic has always been: because institutional investors are optimistic about Bitcoin's future prospects, they buy Bitcoin through Grayscale as a compliance channel.

However, the more accurate situation is: because Grayscale is "profitable," institutional investors are buying in large quantities. Here, "profitable" is not related to Bitcoin's future prospects but rather indicates that there is arbitrage space within the product itself.

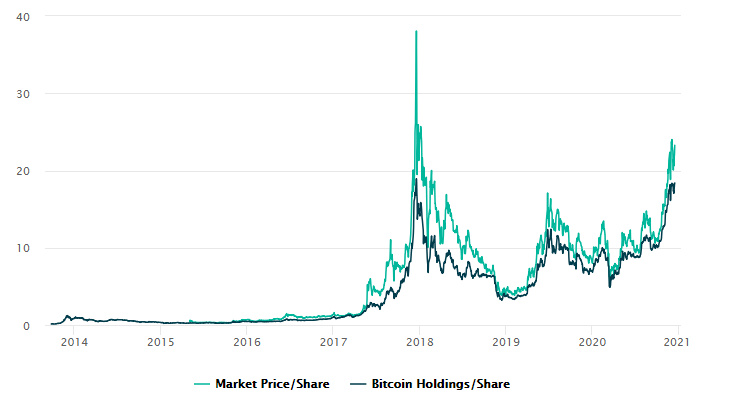

The arbitrage space here mainly comes from the high premium that Grayscale funds have. Taking GBTC as an example, as shown in the chart below, the secondary market price of GBTC moves in line with Bitcoin prices, but the secondary market price of GBTC is far higher than its net asset value, maintaining around 20% for nearly a year.

For general ETF funds, there will not be a high discount or premium due to the arbitrage mechanism of ETFs:

- When net asset value > market price, arbitrageurs will buy ETF shares in the secondary market and then redeem the underlying assets (such as a basket of stocks or other assets) in the primary market using ETF shares, profiting from the price difference;

- When market price > net asset value, arbitrageurs will purchase ETF shares in the primary market using the underlying assets and then sell ETF shares in the secondary market, profiting from the price difference;

So why does Grayscale have a high premium? The reason lies in the fact that Grayscale is a "stripped-down" ETF fund. Due to the cancellation of the redemption mechanism and the requirement to lock in shares for 6 or 12 months, the arbitrage mechanism is not smooth, leading to the phenomenon of high premiums.

Returning to the beginning of the article, Leonardo's famous saying: by creating demand, people are willing to buy stocks. The same applies to Grayscale, which artificially creates a high premium phenomenon to attract investors to purchase Grayscale funds. This is the reason why investors favor Grayscale, unrelated to Bitcoin itself.

Thus, we see a rare scene in the cryptocurrency market where money is made "while standing," gaining a good reputation while also earning substantial profits:

(1) Grayscale, without a redemption mechanism, can only buy BTC but not sell, permanently locking in shares, which is beneficial for BTC price increases; even if not purchased with physical assets, it brings a massive influx of funds into the cryptocurrency market; withdrawals are entirely borne by the traditional capital market, avoiding selling pressure on the cryptocurrency market.

(2) The biggest concern for fund products is redemption risk, but Grayscale, without a redemption mechanism, means it can charge a 3% annual management fee "indefinitely."

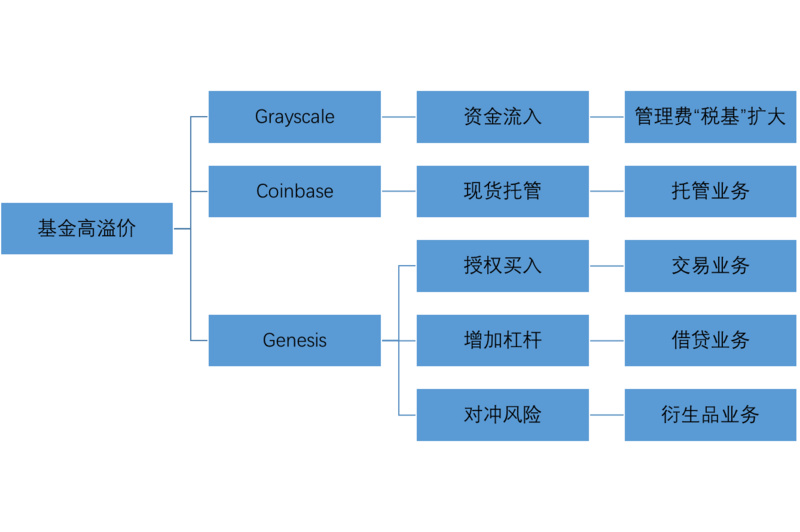

Of course, this artificially created demand not only brings enormous profits to Grayscale itself but also generates significant external effects for Genesis, which is also part of the DCG Group.

Currently, Genesis mainly includes four major businesses: trading, lending, derivatives, and custody. Apart from the recently established custody service, the other three major businesses of Genesis can benefit from the recent rapid growth of Grayscale.

First is the trading business; cash purchases of Grayscale in the primary market are all authorized to Genesis to buy BTC in the spot market.

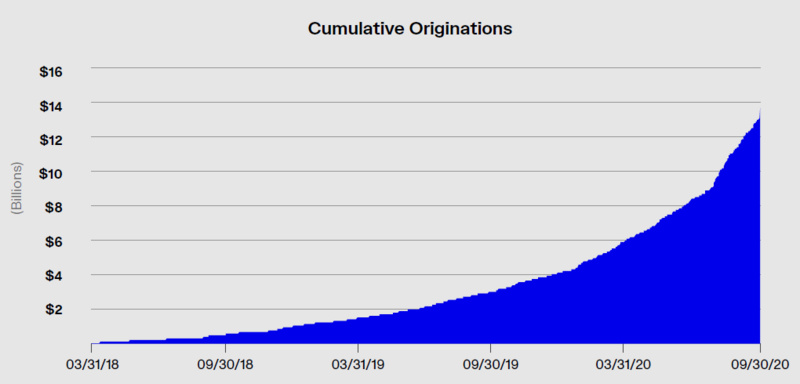

Second is the lending business. Unlike other cryptocurrency lending platforms, Genesis can directly pledge GBTC/ETHE to borrow BTC/ETH. This means investors can use their fund shares for lending and then purchase more fund shares to amplify leverage and increase returns. As long as the high premium in the secondary market exceeds the management fee rate of Grayscale and the lending rate and other additional costs, arbitrage will occur. Similarly, we can observe that since the second half of this year, as Grayscale's scale has continued to expand, Genesis's lending business has also rapidly grown, with a significant increase in cumulative loan issuance.

Finally, the derivatives business, which is often overlooked. Currently, there is a common misconception among investors in the cryptocurrency market: this high premium can be arbitraged through cash/cryptocurrency. The general method is to borrow cash/cryptocurrency from a lending platform and then subscribe to Grayscale's Bitcoin trust shares. After the 6-month lock-up period for the trust shares expires, they can be sold on OTCQX, and if there is a positive premium space, the remaining amount after repaying the principal and interest to the lender is the arbitrageur's profit.

However, the risk of the above arbitrage scheme is quite high, as it does not eliminate the price risk of Bitcoin itself. For instance, if Bitcoin drops by 30% within a month, but GBTC maintains a high premium of 20%, investors would still incur losses. Therefore, for institutional investors, in addition to the above arbitrage operations, they also need to sell corresponding cryptocurrency short in the derivatives market (such as CME, Genesis's derivatives business) to hedge risks.

According to Genesis's third-quarter financial report this year, its derivatives business has become one of the fastest-growing businesses, reaching $1 billion in scale in the third quarter, mainly because clients of Genesis's lending business need to use derivative products for hedging to reduce investment risks.

Similarly, according to the financial report submitted by Grayscale to the SEC, the parent fund of Grayscale holds at least 1% of Coinbase's shares, and all related crypto assets of Grayscale are custodied by Coinbase, which charges custody fees.

From the above, it is clear that Grayscale brings in revenue far beyond just the 3% management fee; it expands the business landscape of the DCG Group. By creating the arbitrage product of "high fund premium," it strengthens Genesis's trading, lending, and derivatives businesses, forming a unique "Grayscale moat" for the DCG Group and creating a "money empire" in the cryptocurrency market.

This article is from a submission and does not represent the position of Chain Catcher. If reprinted, please indicate the source.

Chain Catcher reminds readers to establish a correct understanding of currency and investment concepts, to view blockchain rationally, and to effectively enhance risk awareness; any discovered illegal activities can be actively reported to the relevant authorities.