A Detailed Explanation of How Web3 Aggregation Theory Creates New Markets

Original Author: Joel John

Original Title: 《On Aggregation Theory And Web3》

Compilation: The Way of DeFi

In today's article, I will look at the issue from a broader perspective, viewing Web3 through the lens of Aggregation Theory. This article may be a bit long, but I hope you can stick with it until the end, as we will elaborate on how blockchain investment will evolve over the next decade.

In 2015, Ben Thompson first introduced the concept of Aggregation Theory to explain how the internet has facilitated the evolution of markets. About seven years ago, Ben described Aggregation Theory as follows:

The value chain of any specific consumer market is divided into three parts: suppliers, distributors, and consumers or users. The best way to earn excess profits in these markets is to achieve a horizontal monopoly in one of these three parts or to integrate two of the parts, thereby gaining a competitive advantage in providing vertical solutions. In the pre-internet era, the latter depended on controlling distribution.

The fundamental disruption of the internet has flipped this dynamic on its head. First, the internet enabled the free distribution of digital goods, neutralizing the advantages that distributors had in the pre-internet era by integrating with suppliers. Second, the internet has driven transaction costs toward zero, making it possible for distributors to integrate at scale with end users or consumers.

Image from Ben Thompson's original article in 2015

We believe that this theory is worth re-examining from a new perspective for those working in Web3. We have seen how giants like Ramp, Stripe, and Spotify have been built on the compression of distribution and payment collection costs. But how does this theory apply to Web3 companies? We believe that, in addition to compressing the costs of collecting payments, blockchain can also lower the costs of verification and trust. This makes it possible to create billion-dollar entities that were historically impossible. The new era of blockchain-based aggregators also helps drive innovation at the protocol layer and enables new business models: Hyperfinancialization-as-a-Service. But before that, let's explain Aggregation Theory in detail for those who haven't followed Ben Thompson.

Tightening the Market

Here is an analysis of Uber through the lens of Aggregation Theory. Before Uber, the relationship between sellers (suppliers) and buyers (demand) was limited to local interactions, and the number of customers a driver could have was capped. Additionally, the choices for who could provide ride services were also limited, which is why some drivers could have poor attitudes and still not lose their jobs. Meanwhile, the supply side of the market was chaotic, with a poor reputation, ineffective pricing in many cities, and unpredictable fares. The emergence of Uber organized the supply side.

It is a curated subset of users whose reputations are continuously verified and tracked, rather than a random assortment of drivers. Think about the information you receive every time you request a ride: you know how many rides this driver has completed, the driver's average rating, and the exact amount you can expect to pay.

Why did this shift from taxi unions to app-driven services occur? Because Uber controlled the supply side through their app. Users wanting to book a ride preferred the convenience of hailing a ride remotely rather than waiting on the street and being rejected by randomly appearing taxi drivers. This model works because the internet allowed Uber to establish a risk enterprise from the comfort of their office in San Francisco or any trendy new location and scale globally.

It also enabled Uber to collect payments and reduce costs for itself without relying on regional partners to do so. The rise of digital currency accelerated Uber's adoption; if we were still primarily paying for rides with physical cash, Uber might not have emerged.

Today, the largest companies on the internet can be linked to Aggregation Theory. Companies like Airbnb, Deliveroo, Spotify, Steam, Amazon, and Twitter have disrupted previously chaotic markets through the power of the internet. Aggregators accumulate so much value because they can organize typically large, chaotic markets. Newspapers? There are thousands of newspapers publishing different opinions, often with inaccurate sources. You used a news aggregator instead.

How about renting a house in a small town for a few months? Airbnb made staying in a stranger's home "good." Customers gravitate toward these aggregators because they can expect the same level of service, quality, and standards, with a sufficient list of suppliers available. You get the security of a familiar platform and the choice across the entire market. Returning to the Airbnb example I mentioned earlier, users know they can register on the site and submit a complaint to get a refund if there are issues with their booking. What about Amazon? Refunds are almost instantaneous.

Aggregators make it possible for suppliers' reputations and fair distribution to exist. When you buy something on Amazon, you can check the reviews. In exchange, they take a cut from the transactions that occur on their platform. As a platform digitizes, the frequency of transactions often increases, allowing aggregators to operate at a cost much lower than that of physical experiences. Why? Because the cost of providing digital products (like movie streaming) is just a fraction of that of physical experiences (like flights).

A user can only take one flight at a time. And on the same flight, you might see a user streaming multiple movies. Or, if they are like us, they might purchase countless altcoins or NFTs, perhaps regretting their purchases as soon as they land. I hope that after reading this section, you have a good understanding of what aggregation platforms are and their scale; now let's return to Web3.

Compressing Trust Costs

Just as the internet compressed the costs of distribution and payment collection, publicly verifiable blockchains have also compressed the costs of verification and trust. In fact, all the giants we see in the context of Web3 are built on this principle. Blockchain allows anyone to query and verify whether the digital products being sold truly come from the claimed source. Digital consumer goods sold through blockchain platforms, like NFTs, do not carry counterparty risk because verified smart contracts ensure you receive the exact goods you paid for.

What does this mean for aggregators operating in Web3? It means that the costs of verifying and trusting suppliers when selling digital goods are just a fraction of what they were in Web2. When Netflix or iTunes first launched, they had to spend months or years negotiating contracts to ensure they could enter the market with a sufficiently large inventory of digital goods to attract users.

Even today, Netflix spends about $16 billion internally to produce content based on user data. As these aggregators scale, they become the best places to sell digital consumer goods, having gained this advantage through a decade of effort to secure distribution rights.

However, some interactions are impossible in Web2 aggregators due to siloed databases and non-open data, which introduce inherent friction. For example, you cannot browse property listings on Zillow, make an offer, and refinance the asset all on the same platform. You have to go elsewhere, like Figure, and navigate their various compliance and onboarding processes, which are unique to each platform.

This also makes it harder for developers of other applications and costs more to easily leverage your aggregator and build new interesting services on top of it. On-chain identities, data, and verification standards can solve this problem and make Web3 aggregators more efficient than Web2 aggregators.

In stark contrast, OpenSea does not spend much effort worrying about licensing issues. They can almost instantly verify whether a third-party NFT comes from a legitimate source and track its movement within their user base. What about Uniswap? As long as users accurately add the token's address, there is no need for people to participate in verifying whether the tokens traded on it are legitimate.

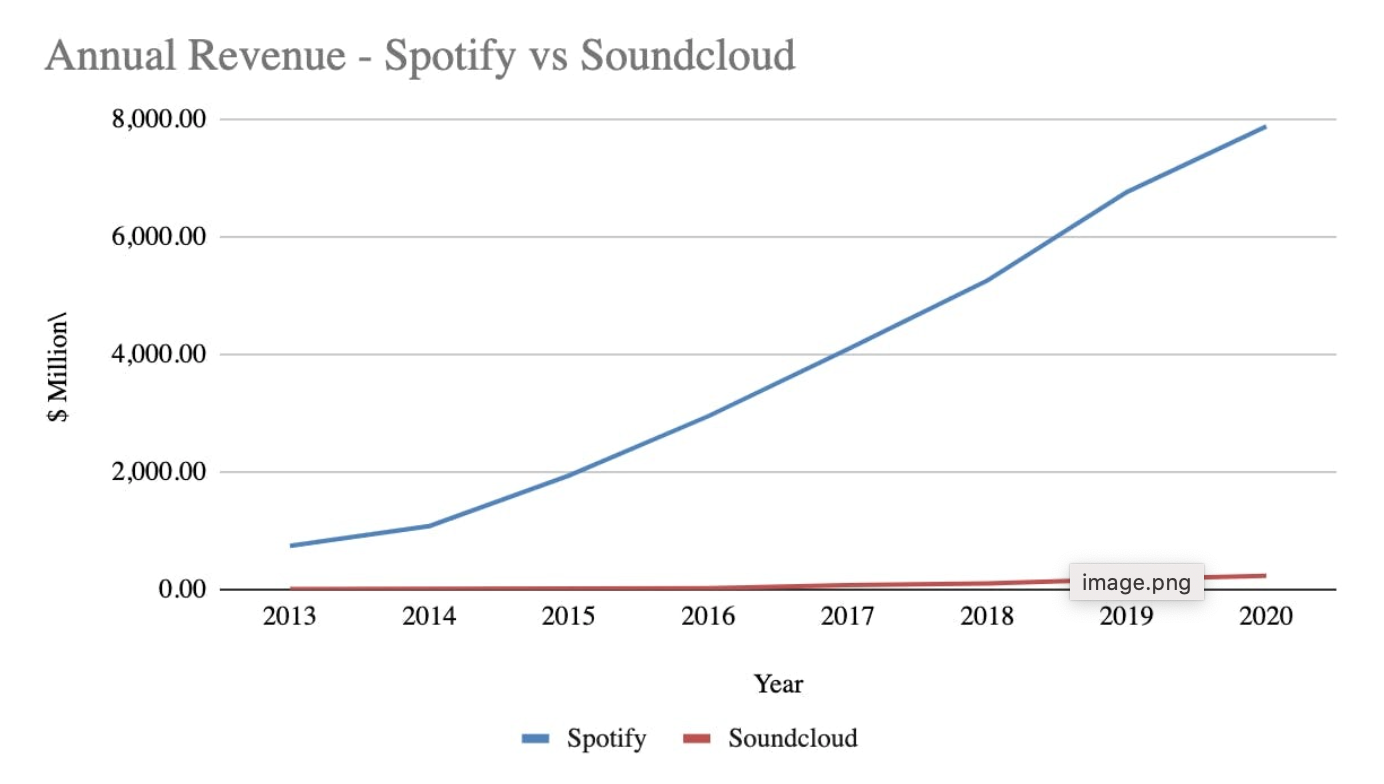

Blockchain abstracts the verification layer and drastically compresses the costs incurred. But does trust itself carry a premium? I believe it does. Let's consider a few examples of platforms that hold commercial rights and compare them with those that do not. Music would be a great topic, so let's use Spotify and Soundcloud as examples.

One is the preferred platform for global music streaming, while the other is occasionally used to find some upbeat music at the gym. By all accounts, Soundcloud is an incredible business because it focuses on community and helping new artists get discovered. However, if you look purely from the perspective of generating revenue, you will notice significant differences between the two businesses.

These two businesses operate differently. Spotify claims to have 406 million monthly active users, of which about 180 million are paid users. Their profit margin is around ±25%, so you can discount the $9 billion in annual revenue calculated in the chart below. But even considering this, you will notice that Spotify's revenue is significantly higher than Soundcloud's.

Part of the reason for this situation is that Soundcloud needs a large number of users streaming to scale its ad-driven revenue. But if all users are on the premium platform, why would they come to Soundcloud? This is a phenomenon you can see across various product categories.

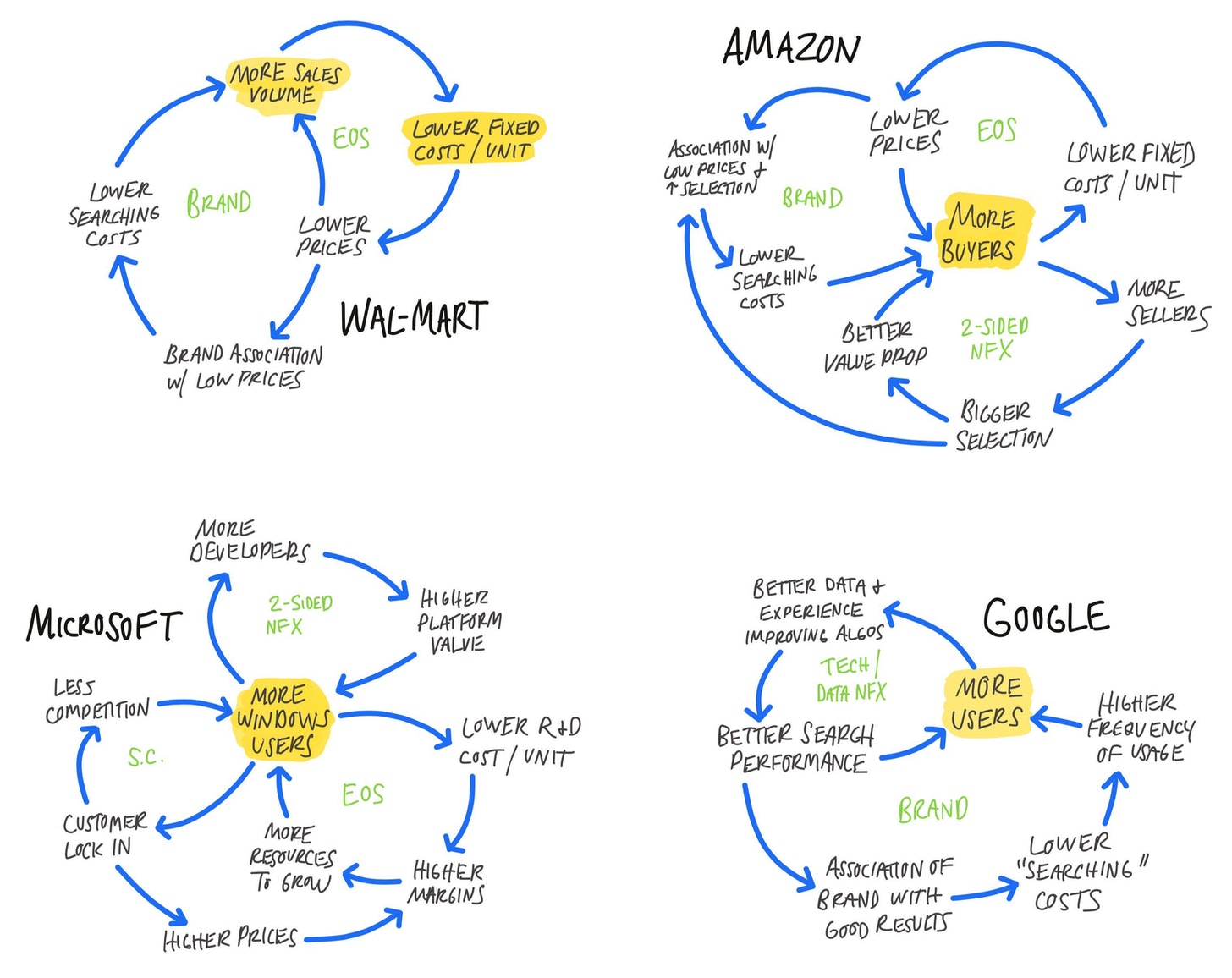

Amazon, as an independent platform, has a larger e-commerce volume than Shopify stores. Steam (the leading gaming platform) generates more revenue than individual game studios. Why? Ultimately, customers choose stores with the greatest selection and the least friction. The more choices available, the more likely commercial activity will concentrate on a single avenue, allowing the platform to offer more choices while maintaining low costs due to economies of scale. This is the flywheel of modern business. Max Olson recently did a great job visualizing these works on Twitter.

Web3 is interesting because it changes the unit economics of verification and trust. Historically, aggregators would acquire the intellectual property rights to the most desirable digital consumer goods. As we will soon see, in emerging markets like India, holding streaming rights for cricket has paved the way for scaling television networks. Blockchain enables platforms to prove the provenance and issuance rights from anyone on the network at an extremely low cost.

This means that expenditures on legal fees and time spent navigating bureaucracies can now be replaced by on-chain verification, identity, and validation. This principle will be key to making aggregators in Web3 immensely powerful. Don’t believe me? Let’s look at some aggregators in the current ecosystem and how they leverage blockchain to their advantage.

Aggregators in DeFi

Zerion is a wallet interface that focuses on enabling users to track their portfolios. The product currently tracks NFTs, allows token swaps, and lets users understand the performance of all tokens in their wallets. Interfaces like those provided by Zerion are rapidly becoming the "homepage" of DeFi. They allow users to interact with complex host applications without connecting to a single website interface. Additionally, these interfaces eliminate the high risks of phishing, lost keys, and signing incorrect smart contracts by allowing users to interact directly through their interface. They help users access features like lending through curated protocols and drive protocol layer innovation by providing competitive prices and features through more choices for customers. It is safe to say that assets worth billions of dollars are currently managed through Zerion's interface.

What is the risk for Zerion? None. They do not hold assets or manage smart contracts. Instead, they are responsible for embedding each of these protocols into their product, forming a super application. According to a recent press release, they interface with about 50,000 assets across 60 protocols. Similar wallet interfaces like DeBank, Frontier, and ImTrust have been at the forefront of enabling more retail participants to find their way in the complex Web3 ecosystem.

How do they do this? They reduce the trust barriers required for users to use applications because end users believe that the interface creators have done their due diligence. Secondly, they allow new applications to be discovered more smoothly than through complex information networks like Twitter. Finally, and most importantly, they combine the fundraising capabilities of multiple DeFi Dapps (decentralized applications) into one interface. As user demand evolves within the industry, they are also beginning to integrate on-ramps and tax software.

I use Zerion as an example here because it is a centralized entity that acts as an interface connecting to multiple DeFi DApps. However, the aggregation functionality in DeFi goes beyond this; here are some examples:

Orderflow ------ 1inch and Matcha.xyz allow users to find the best prices for assets they need to trade without having to go to individual platforms. They do not hold the assets used for trading themselves but seek liquidity from third-party platforms. Matcha has taken this practice a step further by integrating a request-for-quote model into their product. So far, they have completed about $42 billion in cumulative trading volume across approximately 900,000 orders. This feature allows centralized market makers on the backend to quote for large order volumes, making the experience closer to what centralized exchanges like Binance can offer.

Yield ------ The holy grail of DeFi has always been the ability to provide yield. The enormous risk of lending or decentralized exchange platforms is the potential for hacks. But what if you could build an interface that allows users to deploy capital in pools without necessarily holding the assets themselves? Rari, Alpaca, and Yearn Finance do just that. The Rari protocol alone has deployed $922 million through Fuse pools, which is already substantial. Instadapp has taken user experience a step further, allowing users to manage debt positions or deploy assets into yield-generating pools through a single interface. Companies like Maker, Compound, and Aave manage assets worth about $5 billion through their interfaces.

Aggregation in the Metaverse

From the perspective of aggregation, NFTs are fascinating. You essentially have a digital commodity with transactional finality and on-chain proof of intellectual property rights. Please don’t talk bad about me; I will explain this without using technical jargon. Given that users cannot reverse blockchain transactions, users purchasing NFTs almost certainly do not have to worry about being scammed for what they bought unless the NFT itself is a copy.

They can also verify its provenance almost instantly. Unlike the traditional art market, you can almost immediately see what the floor price of an NFT is and who its past owners were. All of this gives NFT aggregators incredible power in their interactions with market participants.

For example, we can look at Gem. This aggregator does not hold any NFTs listed on its platform; they use Dune to provide analytics to users. Once you click on an NFT collection, the interface allows you to bid directly on listings in Opensea and LooksRare. Now, this is where it gets more interesting: aggregators like Gem become the place for price discovery because users are essentially discovering and tracking their portfolios and bidding through them.

In the future, they will also cover functionalities that further blur the lines between DeFi and NFTs through lending and automated inventory management. Traditional art or physical markets have some of the aforementioned limitations related to Web2 aggregators, preventing them from providing these services with low friction and low cost. Additionally, other verticals like gaming and the metaverse do not even have historical analogs—Web3 aggregators will be the first effective markets supporting and realizing these categories of digital assets.

Over time, their influence will be significant enough to determine which NFT collections get "discovered," as they accumulate essentially the market's attention. How much is that attention worth? I don’t know yet, but its value is enough to drive $400 million in transaction volume through the platform. Gem is also influencing the market share of the underlying NFT market itself. Because users are indifferent to the market, as long as there are favorable bids/asks, they will buy and sell assets. For example, since Gem's launch, LooksRare's market share in NFT trading volume has increased compared to OpenSea.

We believe that the aggregation of NFTs connecting assets will occur thematically. For instance, Parcel allows individuals to bid on NFTs tied to real estate. Similarly, there will be separate markets for gambling-related NFTs. Currently, there are still gaps in the NFT markets related to sports, music, and movies. Part of the reason is that thematic focus on asset types allows founders to curate communities around them, creating an initial flywheel for transactions through the platform itself.

Aggregating Data Markets

We have discussed how Aggregation Theory in the context of Web3 creates entirely new markets. The reason the connected aggregation model in Web3 can work is that it primarily focuses on digital assets. There is one area that can be considered more "digital" than tokens and NFTs, which is data markets.

Data markets in Web3 are attractive because:

- All provided datasets can be queried and verified instantly by third parties

- They are directly embedded in multiple third-party applications, allowing for exponential scaling

- The costs of adding each new chain tend to decrease

- The delivery of products (data) is instantaneous

- In the case of protocols, the costs of maintaining network infrastructure are outsourced

You can break this market down into two categories. One is providing direct data access to end users through charts and queries, presenting information in a consumable way. These are centralized businesses like Nansen or Dune. Nansen has built a business by focusing on the interface, with its centralized aspects involving tagging over 100 million wallets and indexing the chains. Users do not create queries themselves; instead, they are handled by Nansen's team, but once the queries for extracting data are created, they can be replicated across chains. Thus, the unit cost of scaling to each new chain tends to decrease. Nansen's initial investment was in tagging and setting up queries for the top holders, smart contracts, or wallet interactions on each chain.

Nansen excels at providing predefined queries for users, while Dune wins by offering infrastructure that anyone can query. Nansen has built its moat based on its extensive work tagging over 100 million wallets, while Dune has established its moat through its broad user base, which is fiercely competing for rankings on its leaderboard.

It is relatively easy for third-party platforms to replicate the data that Dune currently has, but without an active incentive system, it is challenging to replicate community members. The uniqueness of these two platforms lies in their ability to (i) sell data digitally, (ii) conduct sales in almost real-time, and (iii) have limited marginal costs in expanding the number of supported blockchains. Of course, in addition to centralized businesses, there are also protocol-based peers in this space.

Covalent, Graph, Pyth, and Chainlink are alternatives based on the same protocol model. Each of them supports DApps across the entire ecosystem and responds to millions of queries on a regular basis. Data layer protocols are more attractive because they do not necessarily own the hardware infrastructure to make these datasets available. Instead, the indexing of datasets is done within third-party infrastructure, incentivized by the protocol's native tokens. In traditional data businesses, the costs of running infrastructure can eat into a company's profitability. In the case of protocols, the perceived "value" of the network increases with each new node hosting data on these networks, reducing the likelihood of a complete network failure.

The Next Decade of Aggregation

Before concluding, let’s revisit the core argument of this article. We believe that blockchain will facilitate a new category of markets capable of instantaneously verifying on-chain events. This will compress the costs of large-scale verification of intellectual property rights to an extreme, creating new business models. Today's Web3 aggregators provide interfaces that display on-chain data and allow users to interact with smart contracts from multiple platforms. They do not bear the risk of holding these assets and typically do not incur the exponentially high costs of supporting additional networks. Covalent and Nansen can generate exponential value by adding each new chain (which is often a linear expenditure).

In the next decade, the core proposition of Web3 aggregation will be streamlining large, chaotic processes with multiple parties in low-trust systems. One example of this is AngelList. The platform structurally simplifies the friction involved in assembling venture capital rounds by combining legal, banking, and LP (liquidity provider) management into a single interface. How valuable is it? Based on their latest funding round, about $4 billion. Large, chaotic markets with multiple moving parts are challenging to integrate at scale unless you have the time or capital. AngelList took about eight years to establish its monopoly, while Uber had to raise about $25.5 billion to become the giant it is today. I believe blockchain will compress the unit economics around this issue and super-financialize the process. Combining the elimination of inefficiencies in historically long and chaotic processes with incentives that allow people to profit from them can be a powerful combination.

This is already happening in some emerging markets. In the next article, we will introduce a company that executes, verifies, and confirms the stack needed for traditional contracts in Africa. In the context of Web3, aggregation reduces the degree of corruption and inefficiency, and emerging markets historically plagued by corruption and lack of transparency will benefit the most—think of DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations). Today, forming a DAO on Ethereum takes five minutes and costs $200. In stark contrast, I spent six months and made countless phone calls to register a company in India. Part of this delay is due to the lack of trust and the inability to instantly verify my data. Blockchain helps bridge this gap; we are merely providing the manufacturers of trust production machines for societies lacking trust.

P.S.: Feel free to steal this article and remix it. We are looking for in-depth research on how blockchain achieves aggregation in different markets. If you have any thoughts on this, come discuss it in our Telegram.

Disclosure: The author of this article has invested in some of the projects mentioned above.