Comprehensive Analysis of Cross-Chain Bridges: Design, Trade-offs, and Opportunities

From: Amber Group

Compiled by: Odaily Planet Daily

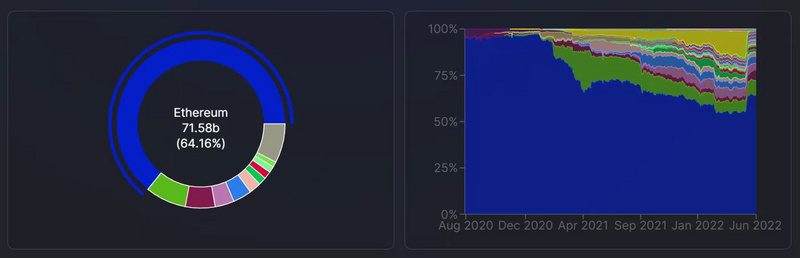

Last year, Ethereum, as a mainstream smart contract blockchain, faced challenges to its dominance from alternative L1 blockchains. The multi-chain world has become an undeniable reality. With the introduction of these new chains, their heterogeneous consensus mechanisms, smart contract languages, and community values will split Web3 into various ecosystems.

L1 Blockchain Market Share (calculated by aggregated TVL proportion)

Source: Defi Llama

These separated ecosystems create value for their respective communities, but the lack of interoperability between them results in the loss of most cross-chain collaborative value. This fragmentation has also led to a rise in tribalism, increased attack vectors, and a deterioration in user experience.

To promote industry development and attract billions of new users, friction between chains must be reduced. This is the primary goal of crypto cross-chain bridges.

This report will cover the definition of cross-chain bridges, classifications of different cross-chain bridge architecture designs, trade-offs between different designs, risks associated with cross-chain bridges, and our views on the prospects of the cross-chain bridge ecosystem.

Definition and Classification of Cross-Chain Bridges

In the broadest sense, cross-chain bridges transfer information between two or more blockchains. This function is most commonly used to exchange assets on one blockchain ("source" chain) for assets on another chain ("target" chain). At the same time, cross-chain bridges can also be used to transmit data or messages from the source chain to the target chain. As of the writing of this article, there are over 100 cross-chain bridges currently in use to transfer information within Layer 1 and Layer 2 ecosystems.

This increasingly complex environment makes it difficult for new participants to understand the sector, so establishing an overall framework to simplify various designs may be helpful. Recently, Arjun Chand constructed a useful framework that categorizes various types of cross-chain bridges into different categories. We also adopt a similar approach to classify the diverse cross-chain bridges.

Cross-chain bridges can be classified based on various characteristics. These characteristics include the method of cross-chain information transfer, trust assumptions, and the types of connections involved.

We believe the most important characteristic is how cross-chain bridges transfer data from one chain to another.

Cross-Chain Mechanisms

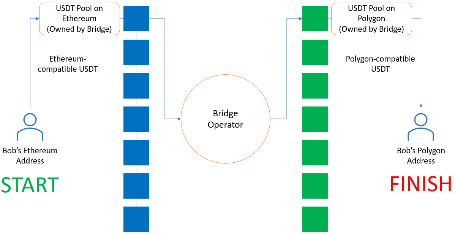

Liquidity Pool Model Cross-Chain Bridges

To understand how liquidity pool model cross-chain bridges work, let’s imagine a user who wants to transfer USDT from Ethereum to Polygon. The user first deposits the Ethereum version of USDT into a designated contract address (liquidity pool) on Ethereum and specifies the receiving address for that USDT on Polygon, which is the address where USDT will be credited on Polygon. The cross-chain bridge uses this information to transfer the Polygon version of USDT to the specified Polygon address.

Bridging Mechanism of Liquidity Pool Model Cross-Chain Bridges

One major drawback of this design is that the cross-chain bridge must ensure that there are sufficient assets in its unilateral liquidity pool on the target chain for the user to complete the fund transfer. In the example above, if the cross-chain bridge's USDT liquidity pool on Polygon is empty, the USDT stored in the Ethereum liquidity pool will be "stuck" until another user requests a reverse transfer of USDT from Polygon to Ethereum, and sufficient USDT is added to the USDT liquidity pool on Polygon.

Additionally, this type of cross-chain bridge only allows for the transfer of a single type of asset across chains (for example, only transferring USDT from Ethereum to Polygon). If the user wants to exchange USDT on Ethereum for MATIC on Polygon, they can only do so after receiving USDT on Polygon.

The main advantage of this design is that once users receive tokens on the target chain, they no longer need to rely on the security of the unilateral liquidity pool. The assets received by the user are native assets on the target chain, so there is no need to depend on the redemption capability of the underlying asset to ensure the value of their assets. This contrasts sharply with another commonly used bridging design of "lock & mint / burn & redeem."

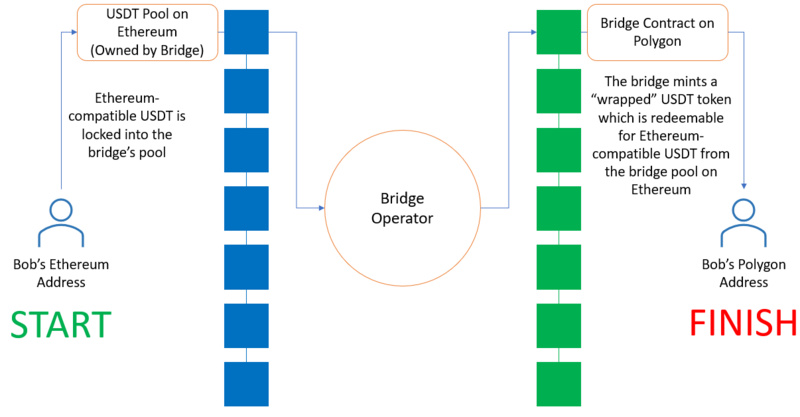

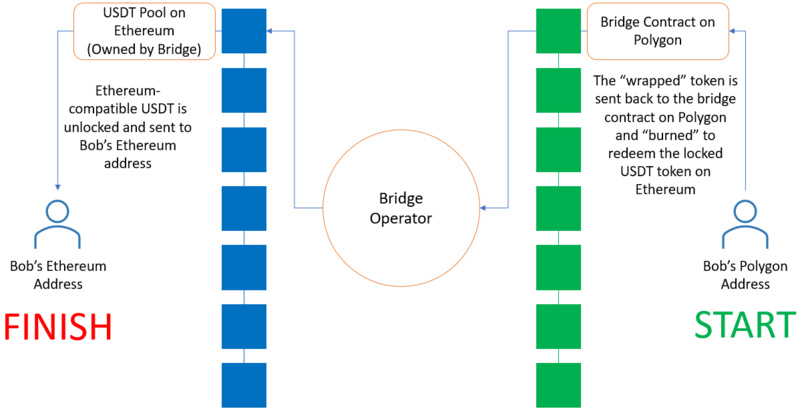

Lock & Mint / Burn & Redeem

Another common type of cross-chain bridge uses a "lock" or "burn" mechanism, followed by minting or redeeming. Let’s again use the example of transferring USDT from Ethereum to Polygon to describe how this mechanism works. As before, the user first deposits the Ethereum version of USDT into a designated contract address held by the cross-chain bridge and specifies a receiving address on Polygon. This step is referred to as "locking."

However, unlike before, this type of cross-chain bridge "mints" or issues the Polygon version of the deposited asset on Polygon and credits it to the receiving account. These minted tokens are usually referred to as "wrapped" tokens, and their value depends on the ability to redeem them for the underlying asset on the source chain. When the user wants to transfer back to Ethereum, the wrapped tokens are simply sent to the cross-chain bridge contract address on Polygon and "burned." This allows the underlying asset on Ethereum to be redeemed and sent to the specified receiving address.

Locking USDT to Mint Wrapped USDT

Burning Wrapped USDT to Unlock USDT

(i.e., the reverse of the minting transaction)

Since wrapped tokens rely on their redeemability to maintain their value, holders of wrapped assets face smart contract risks. If the liquidity pool on the source chain is compromised and the underlying assets are drained, the wrapped tokens will become worthless. This is exactly what happened in the recent attack incident on the Wormhole cross-chain bridge, which resulted in losses exceeding $320 million.

Nonetheless, the advantage of the lock/burn & mint mechanism is that such cross-chain bridges always allow for smooth asset transfers from the source chain to the target chain and vice versa. This is because they do not require deploying liquidity token pools on the target chain within the cross-chain bridge contract. This gives this type of cross-chain bridge an advantage in scalability.

Native Cross-Chain Swap Bridges (with Decentralized Intermediate Chains)

Over the past year or so, this type of cross-chain bridge has become increasingly popular, with the growth of the THOR chain being one of the contributing factors. Native cross-chain swap bridges allow users to swap native tokens on the source chain for different native tokens on the target chain. For example, users can exchange native BTC for native ETH on their respective chains without needing to wrap the assets. This is achieved by utilizing cross-chain automated market makers (AMMs) and intermediate chains that monitor and record the states of the source and target chains. Although the ability to swap different native assets across chains is very useful, this type of cross-chain bridge employs one of the most complex transfer mechanisms.

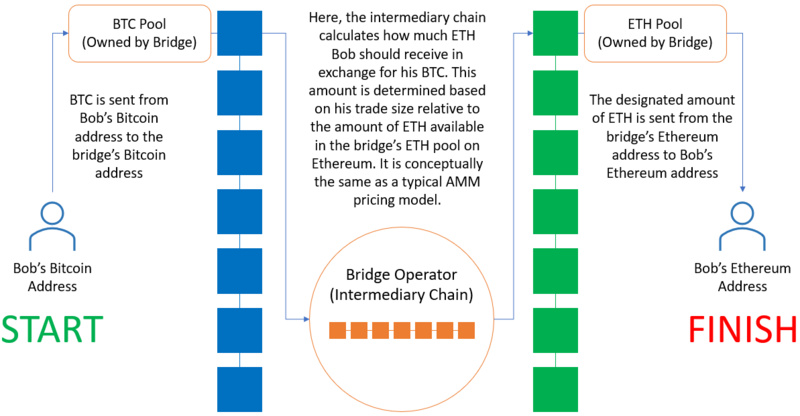

To simply explain how it works, let’s look at an example of exchanging native BTC for native ETH, using a basic version of the THOR chain architecture as a reference.

Exchanging Native BTC for Native ETH via Decentralized Intermediate Chains and Built-in AMM

In this example, a user holding BTC first sends BTC (along with their Ethereum receiving address) to a Bitcoin vault address. This vault is controlled and monitored by multiple nodes that observe incoming transactions and record updates to the Bitcoin vault's state on the intermediate chain (e.g., THOR chain).

Once the nodes confirm that the vault has received BTC, they will calculate the appropriate amount of ETH to credit to the user on the Ethereum blockchain. Similar to any other AMM exchange, the execution price of the cross-chain swap depends on the amount being exchanged, which relates to the respective amounts of BTC and ETH available in the vaults on both chains. Large swaps that "deplete" a significant amount of liquidity will execute at a higher price compared to smaller swaps using minimal liquidity. Once the exchange amount is calculated, the intermediate chain sends a message to the Ethereum network to transfer the appropriate amount of ETH from the vault address to the user's receiving address.

Compared to liquidity pool model cross-chain bridges, native cross-chain swap bridges with intermediate chains offer a higher level of decentralization and censorship resistance. For cross-chain bridge users, while liquidity providers can still steal assets from the AMM's liquidity pool through hacks or vulnerabilities, it can avoid the smart contract risks associated with wrapped assets.

Despite these advantages, this type of cross-chain bridge is far more complex in architecture than other cross-chain bridges. Creating a trusted decentralized native cross-chain swap bridge requires significant capital and time investment. For example, to achieve native exchanges from BTC to ETH, each node on the THOR chain must run a full Bitcoin network node as well as a full Ethereum network node. Additionally, each node on the THOR chain must be incentivized to remain honest and reliable. All of the above must be completed for a single exchange.

Native Cross-Chain Swap Bridges (Using Stablecoins as Intermediaries)

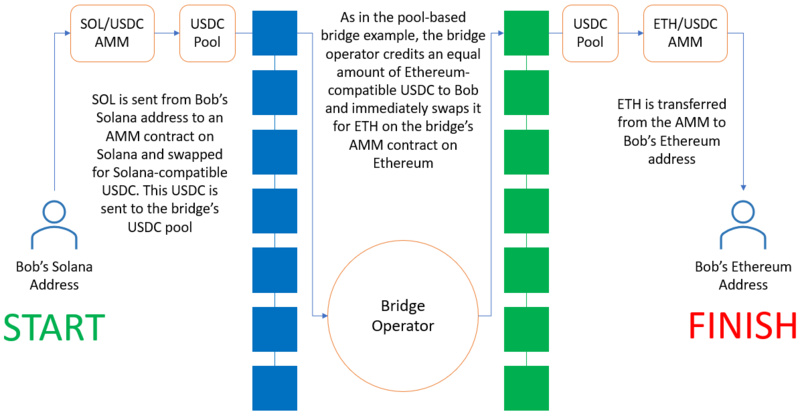

This type of cross-chain bridge aims to borrow the simple architecture of liquidity pool model cross-chain bridges while providing the convenience of swapping native assets. Essentially, this type of cross-chain bridge operates similarly to liquidity pool model cross-chain bridges but adds an extra step that allows users to receive assets on the target chain that can be different types of assets from what they deposited on the source chain. LayerZero Labs' Stargate cross-chain bridge is an example of this type. We will use another example to explain how it works. This time, let’s consider exchanging native SOL for native ETH.

Exchanging Native SOL for Native ETH Using Two AMMs and a Cross-Chain Stable Swap Bridge

Again, the user first deposits their SOL asset into a designated contract address on Solana held by the cross-chain bridge. However, unlike the previous example, this deposit actually triggers the AMM to swap SOL for a stablecoin on Solana. For example, it might swap SOL for USDC. From this point, the functionality of the cross-chain bridge will be extremely similar to that of the liquidity pool model cross-chain bridge. The stablecoin balance in the Solana contract address is transferred by the cross-chain bridge provider to the user's contract address on Ethereum.

Finally, once USDC is credited to the user's account on Ethereum, the cross-chain bridge triggers the AMM to execute the swap from USDC to ETH. This ETH is then credited to the user’s specified receiving address. Essentially, the functionality of this type of cross-chain bridge is comparable to that of the liquidity pool model cross-chain bridge, except that it only transfers stablecoins across chains to provide better execution prices during the cross-chain transfer process. Typically, the execution price for AMM swaps on both chains is derived from a function that calculates the scale of the swap amount, which is related to the available liquidity in the two unilateral pools.

This architecture avoids the smart contract risks associated with wrapped assets and provides a simpler cross-chain communication mechanism than intermediate chain architectures. However, since the execution price depends on the available liquidity of each AMM, there is a risk of suboptimal execution prices.

Message Transmission via Master (Home) Contracts / Replica Contracts (Using Optimistic Fraud Proofs)

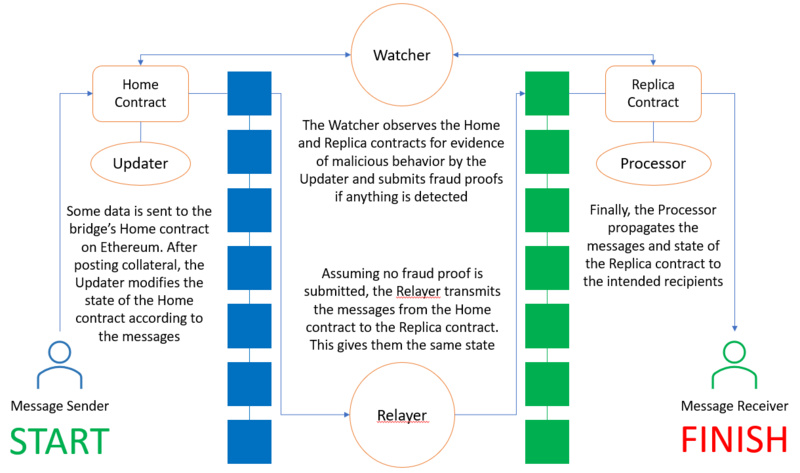

This special type of cross-chain bridge utilizes two contract addresses located on different chains (referred to as the master contract and the replica contract) along with four incentivized off-chain participants to achieve cross-chain message sending. The most well-known protocol in this category is Nomad, which enables multi-chain applications to communicate more easily across blockchain ecosystems. Let’s explain how it works through a simplified example of sending a message from Ethereum to Polygon:

Master contract and replica contract updated, monitored, and propagated by incentivized off-chain participants to achieve cross-chain message sending

A user on Ethereum first submits a message to the master contract address on Ethereum. The master contract collects this message and queues it along with other received messages. At this point, an off-chain participant known as an "updater" signs the group of messages to update the state of the master contract. To sign these messages, the updater must stake a bond with the master contract, which will be forfeited if it is later proven that the updater acted maliciously. The second off-chain participant is the "observer," who monitors the master contract and the replica contract on Polygon to ensure that all messages are correctly recorded and sent.

Since the cross-chain bridge relies on optimistic fraud proofs, the observer is responsible for submitting proof of malicious behavior to prevent malicious actions from being executed and to punish malicious updaters. In the absence of proof of malicious behavior, the cross-chain bridge assumes that the messages have been correctly recorded and sent (hence the name "optimistic"). Assuming the observer does not detect any issues with the updater's operations, the third off-chain participant, the "relayer," will transmit the message to the replica contract on Polygon. Finally, the fourth off-chain participant, the "processor," propagates the message from the replica contract to the final recipient of the message.

This architecture is better suited for message/data transmission between blockchains, but since asset transfers ultimately reflect changes in account balances as data, this architecture can theoretically also be used for asset transfers.

One major drawback of this bridging design is the sustained delay of approximately 30 minutes for fraud proof (DTD), which provides a window for observers to scan for suspicious behavior and challenge malicious transactions. Protocols like Connext and Hop shorten the waiting time by allowing other market participants to send tokens directly to the final recipient before the fraud proof window closes. In practice, these two protocols take on the risk of malicious transactions for the recipient, charging fees from recipients seeking higher liquidity.

Trust-Based vs. Trustless

In this classification, cross-chain bridges are divided into two categories. They are either 1) trust-based or 2) trustless. In other words, users either trust a third party to operate the cross-chain bridge and ensure security, or they rely on distributed software design and operation, so that no single entity can change its state or operate it. Trust-based cross-chain bridges include xPollinate, Matic Bridge, and Binance Bridge. Trustless cross-chain bridges include THOR chain, Ren, and Cosmos IBC.

It is important to note that the distinction between trust-based and trustless is not black and white, but rather a gradient. Compared to systems with a larger and more heterogeneous set of operators, distributed software protocols with smaller operator sets or geographically concentrated distributions are more susceptible to single points of failure. Similarly, cross-chain bridges that require users to lock assets in contract addresses in exchange for wrapped assets also require users to trust that the code is written in a way that prevents attacks or theft. Non-custodial cross-chain bridges do not require this trust, even though they are often operated by centralized entities.

What Are the Connection Objects?

From Layer 1 to Layer 1

Cross-chain bridges from Layer 1 to Layer 1 allow users to transfer funds between two L1 ecosystems. For example, Wormhole's Portal cross-chain bridge supports asset transfers from Solana to Ethereum. By facilitating interoperability between Layer 1 ecosystems, web3 users can freely spend time and resources on their preferred chains while retaining the flexibility to switch chains at any time.

From Layer 1 to Layer 2

Cross-chain bridges from Layer 1 to Layer 2 allow communication between L1 chains like Ethereum and L2 chains built on L1. For example, a user may want to transfer ETH from the Ethereum mainnet to Arbitrum, Optimism, or ZkSync. Users can transfer their tokens using the native cross-chain bridges of each L2 or can use third-party cross-chain bridges like Across. As the L2 ecosystem continues to grow, these types of cross-chain bridges will play an important role in transferring activities from the Ethereum mainnet to L2.

From Layer 2 to Layer 2

As the first half of 2022 drew to a close, the Layer 2 roadmap became increasingly clear. Various Layer 2 scaling solutions from Polygon (Miden, Hermez, Nightfall), Starkware's zero-knowledge rollup Starknet, and Matter Lab's ZkSync 2.0 will provide developers with the necessary building blocks to create applications unburdened by high gas fees. However, these different L2s are not inherently compatible, and they may present the fragmentation we see in L1. The L2 ecosystem benefits from high throughput, low gas fees, and strong security, and cross-chain bridges from L2 to L2 aim to reduce potential fragmentation between L2s while promoting the aforementioned benefits of L2. Some projects, including Hop Protocol and Orbiter Finance, are actively working towards this goal.

Trade-offs in Cross-Chain Bridge Design

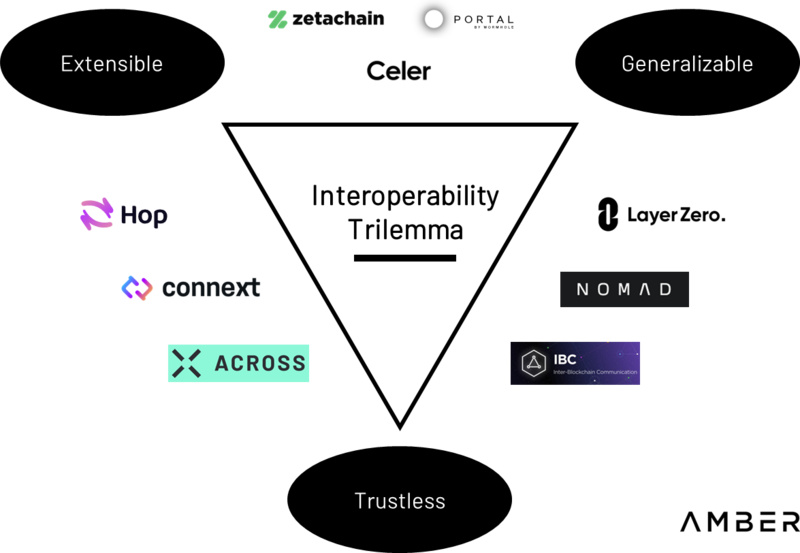

Despite the dozens of architectural designs for cross-chain bridges, no single cross-chain bridge can possess all three attributes of the "interoperability trilemma". The interoperability trilemma is a term coined by Arjun Bhuptani, which states that cross-chain bridges can only have two of the following three attributes: universality, scalability, and trustlessness.

1. Universality: The ability to transmit arbitrary data between two chains.

2. Scalability: The ability to deploy quickly on heterogeneous chains.

3. Trustlessness: Minimizing trust assumptions.

Interoperability Trilemma

Source: Arjun Bhuptani

Similar to the scalability trilemma, when a cross-chain bridge chooses two of these attributes, the last attribute becomes difficult to satisfy. For example, Connext is a trustless cross-chain bridge that can transfer tokens between two EVM-compatible chains. Currently, it cannot transmit arbitrary data, meaning it prioritizes scalability and trustlessness over universality. Other cross-chain bridges like ZetaChain prioritize scalability and universality but require an additional layer of trust provided by the validator set of the cross-chain bridge, sacrificing trustlessness.

Since the primary use case for cross-chain bridges is the transfer of tokens between two blockchains, most projects choose universality and scalability to enable rapid deployment across heterogeneous chains while maintaining flexibility in transmitting arbitrary data. This allows this type of cross-chain bridge to complete deployments faster than many competitors and meet the market demand for token transfers. While this incurs hidden costs for many of their users (which will be discussed in the risks section), this type of cross-chain bridge can expand its application scenarios from executing simple token transfers to more comprehensive developer platforms.

To describe the transition of cross-chain bridges from token transfer mechanisms to application platforms, we can use an analogy: cross-chain bridges are like toll roads connecting two highly congested cities. Every time a user wants to drive from City A to City B, the toll road charges a fee. Cross-chain bridges have been gradually shifting this toll road model towards a town model, where developers build applications on the cross-chain bridge, akin to creating a town between City A and City B.

A large town (ecosystem) will eventually develop at the toll booth (cross-chain bridge) connecting different cities (blockchains)

Because some cross-chain bridges have tens of thousands of independent users and have achieved billions of dollars in transfer volumes, they can leverage existing user activity to incentivize developers to build applications on their cross-chain bridges. Continuing with the toll road analogy, developers are like ambitious entrepreneurs who decide to move to the town after witnessing wealthy individuals (users) flock to the area. After observing more developments in the town, other entrepreneurs also move in and start creating larger-scale businesses (applications). Soon, the town flourishes, and the toll booth that once served as a transportation medium between two major cities now becomes the gateway to this thriving town.

Cross-Chain Bridges as Application Platforms or "Layer Zeros"

There are several noteworthy projects attempting to become the thriving town depicted in the previous analogy. These projects focus on developing new methods for cross-chain connectivity while providing the foundation for the dapp ecosystem. These projects include:

RenVM

RenVM and the Catalog protocol are akin to the toll road and town in the above example. RenVM supports cross-chain transactions using the previously described "lock and mint / burn and redeem" mechanism. Currently, it allows users to move BTC in and out of Ethereum and Polygon using the wrapped BTC token "renBTC" as an intermediary. The cross-chain bridge can be seen as an application built on top of RenVM. On top of this, Catalog is a pioneering protocol promoting RenVM modules, building automated market maker (AMM) solutions within RenVM. Catalog is the first protocol ever built using the "borderless liquidity" mechanism. This AMM design not only utilizes Catalog's own liquidity pool but also leverages liquidity pools from third-party DEXs, regardless of which chain they are on. In this example, Catalog collaborates with RenVM and its existing user ecosystem to provide more complex transaction types within a familiar user experience.

LayerZero

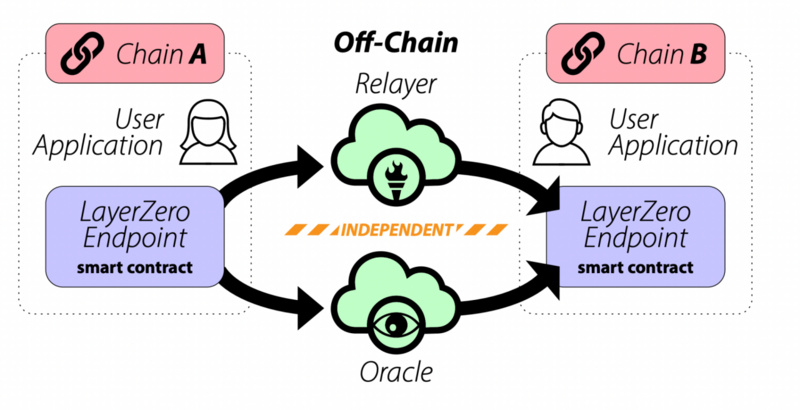

LayerZero is a communication primitive that allows data and information to be sent across EVM chains with LayerZero endpoints. LayerZero endpoints are essentially on-chain clients. Any chain with ZRO endpoints can conduct cross-chain transactions. Third-party oracle services, such as Chainlink, are required between endpoints to serve as a security mechanism for transactions and message passing.

LayerZero ensures the validity of cross-chain communication by requiring two independent entities (Oracle and Relayer) to confirm transactions

Source: LayerZero Whitepaper

Applications deployed on various L1 blockchains will find this a very straightforward approach. For example, if a Dapp is built on Polygon, using endpoints to quickly load this Dapp onto LayerZero is a relatively simple task. Decentralized applications like Stargate utilize the communication standards set by LayerZero to create decentralized exchanges/cross-chain bridges.

Zeta Chain

Zeta Chain is a Layer 1 blockchain that does not require wrapped assets for cross-chain asset transfers, nor does it require a cross-chain bridge for each pair of blockchains. This is achieved through Zeta Chain's ability to pass messages across chains, allowing data and value to be sent across chains and layers. By utilizing full-chain smart contracts, developers can program Zeta Chain to listen for events on connected blockchains and execute corresponding actions. Zeta Chain relies on validator node consensus to ensure its security and employs a distributed threshold signature scheme to secure private keys on connected chains, thus avoiding single points of failure. PoS incentivizes validators to act correctly.

What sets Zeta Chain apart from other competitors like LayerZero is that even non-smart contract blockchains, such as the Bitcoin network, can be integrated into the multi-chain network.

These cross-chain bridge platforms achieve interoperability between chains and allow for the establishment of new ecosystems on top of them. In addition to sending tokens from chain A to chain B, they unlock new application scenarios. Nevertheless, each unique mechanism of cross-chain bridges/cross-chain bridge platforms carries a certain degree of risk.

Risks Associated with Cross-Chain Bridges

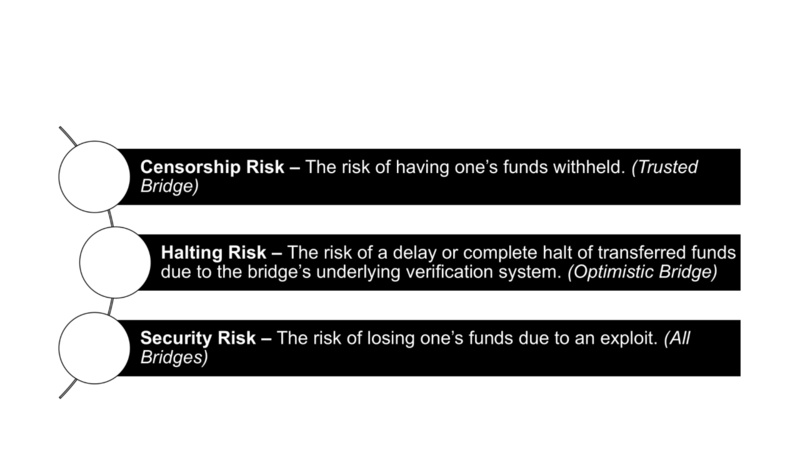

Given the technical complexities involved in enabling message passing for cross-chain transfers, using cross-chain bridges involves various risks. Some major risks include:

Risks of Cross-Chain Bridges

To mitigate censorship and halt risks, users can simply use fewer trust-based cross-chain bridges and "optimistic" cross-chain bridges. However, security risks can never be completely avoided, so it is crucial to assess which security systems are stronger by understanding potential attack vectors.

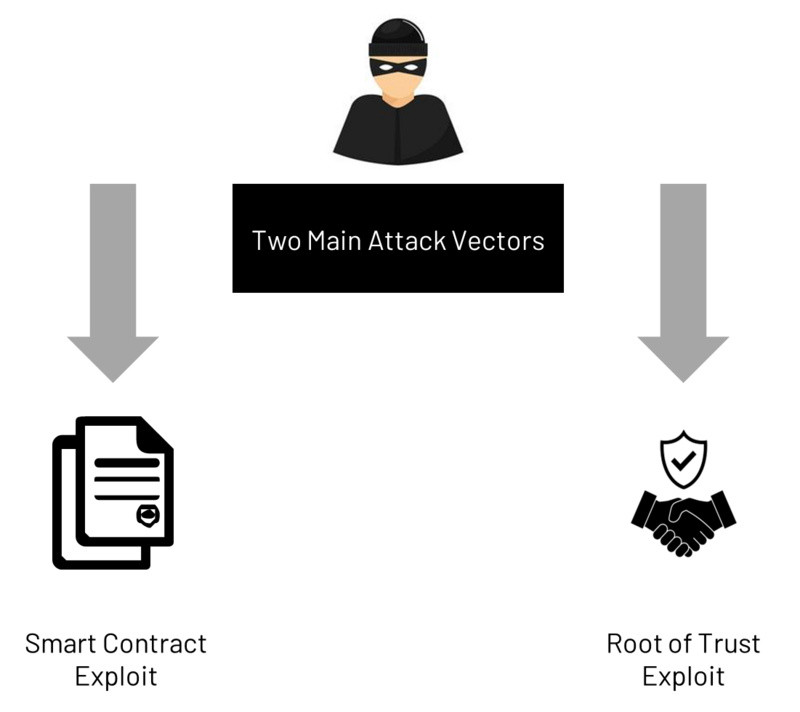

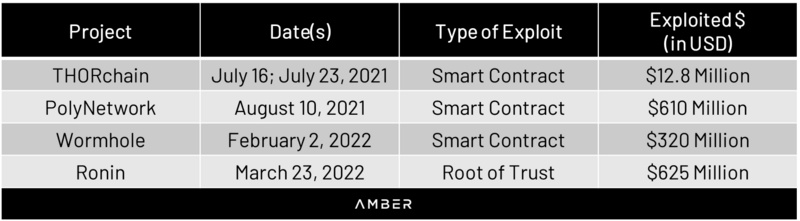

The two main attack vectors that compromise the security of cross-chain bridges are 1) smart contract vulnerabilities and 2) trust root vulnerabilities.

Two Main Attack Vectors for Cross-Chain Bridges

Malicious actors exploit smart contract vulnerabilities when successfully attacking cross-chain bridges at the application layer. Since most cross-chain bridges must deploy secure smart contracts on all chains they connect, newer blockchains are easier targets for attacks.

While languages like Rust, CosmWasm, and Substrate have growing developer communities, they do not have as many developer tools and auditing firms as more mature languages like Solidity, making it more likely for mainnet vulnerabilities to occur. Considering that teams developing cross-chain bridges will weigh factors like development speed and market competition, it is easy to understand why smart contract vulnerabilities become the most common attack vector for hackers.

As for exploiting trust root vulnerabilities, malicious actors need to successfully attack the underlying verification methods used by cross-chain bridges. In the Ronin hack incident, malicious attackers compromised the private keys of 5 out of 9 validators of Sky Mavis, the studio behind Axie Infinity, to execute an attack on most honest assumptions. Once the hacker infiltrated Sky Mavis's centralized security system, everything fell apart.

As seen, these vulnerabilities are not easily detectable externally, but the costs associated with poor security systems can be enormous. Last year, the cumulative cost of cross-chain bridge attacks exceeded $1.5 billion.

Notable Cross-Chain Bridge Exploit Incidents in the Past Year

Sources: Decrypt, Kudelski Security Research, The Verge, VentureBeat

To make matters worse, unsuspecting web3 users can easily feel that cross-chain bridges with higher TVL/TVB are safer, as these bridges seem strong enough to handle large amounts of token transfers; however, there is no clear correlation between TVL/TVB and security. In fact, one might argue the opposite: as TVL/TVB increases, the economic incentives for malicious actors to exploit vulnerabilities also grow, thus increasing the security risks faced by cross-chain bridges.

Therefore, when transferring funds, it is advisable to understand the underlying security systems used by the cross-chain bridge. If a casual trader needs to quickly send 0.5 ETH to ensure the completion of an NFT minting, security may be of little concern. However, if a DAO plans to transfer 10,000 ETH to a contract on a different chain, it is necessary to carefully examine the underlying security of the cross-chain bridge.

Conclusion

As the crypto industry continues to evolve, new cross-chain bridge designs will be explored, new security models will be tested, and entirely new applications based on cross-chain bridges will emerge. The successful emergence of cross-chain bridges that combine security, flexibility, and efficiency will allow for broader interconnectivity between protocols and communities. While we are currently in a period of filtering and eliminating unsafe cross-chain bridges, the future of the cross-chain bridge industry will be bright.