A Long Article: Analyzing the Underlying Logic of Web3 from the Perspective of Institutional Economics

Original Title: "The Underlying Logic of Web3: A Perspective from Institutional Economics"

Author: Kokii, Dim Orange Segment

TL; DR

- Web3 is a new economic infrastructure for coordination and exchange. It starts with fundamental property rights systems, shifting trust in complex institutions from individual organizations to decentralized nodes and verifiable code. It has unique economic characteristics that allow it to complement and, in some cases, compete directly with existing mechanisms.

- Institutional economics is a subset of economics that studies the role of institutions in socio-economic contexts using economic methods, with fundamental theoretical tools being transaction cost theory and property rights theory.

- Tokens are a property management tool that can represent any existing digital or physical asset, or access rights to others' assets. On-chain tokens can achieve cryptographic property protection, competitive property innovation, and efficient property circulation.

- Smart contracts are agreements guaranteed to be automatically executed by code. As property rights systems become more granular and refined, many components of economic activities, including repetitive mechanical parts in production and transactions, calculative rules, and order, may be replaced by machines and smart contracts.

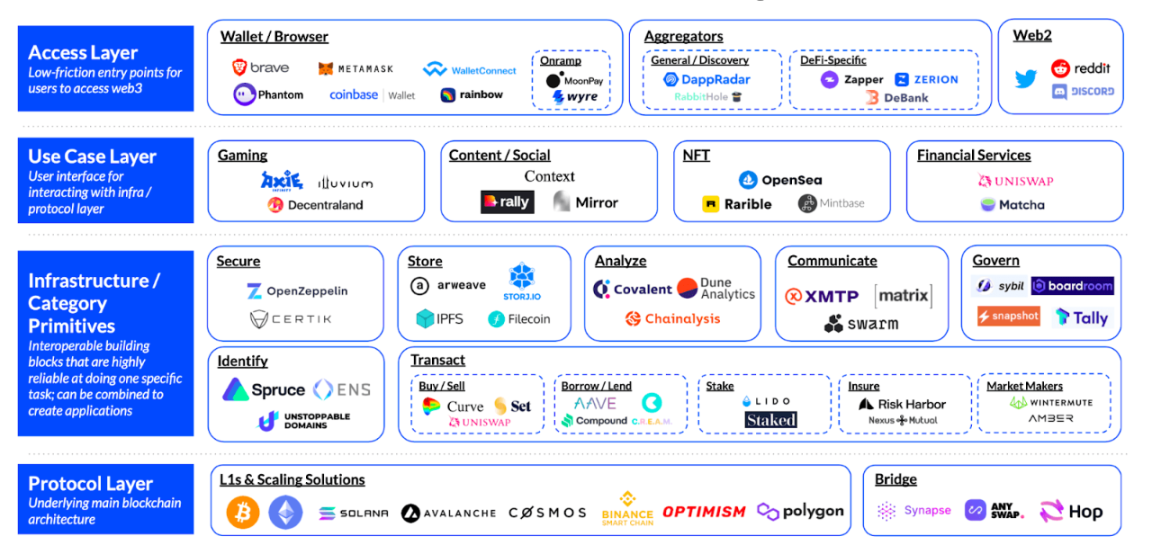

Why Think About the Underlying Logic of Web3

The current Web3/Crypto space is filled with various new terms, making this already obscure new industry even more confusing. From technical/application terms like consensus algorithms, Rollup, zero-knowledge proofs, DeFi, NFT, GameFi, DAO, cross-chain bridges, oracles, DID, SBT, to conceptual ideas like cypherpunk, sovereign individual, decentralization, anti-censorship, permissionless, composability, creator economy, distributed governance, value internet, permanent storage, Code is Law, X to Earn, it all sounds bewildering. Coupled with various regulatory bans, ideologies, scams, Ponzi schemes, inefficient and counterintuitive application scenarios, it is hard to grasp the context.

Those who love it say it is the future, a fundamental technological revolution on par with the internet; those who hate it say it is a pile-up of concepts, a capital bubble fabricated by venture capitalists, a self-entertainment of libertarians.

Focusing on details can hinder one's ability to see the big picture. When the internet was first adopted by a small group of geeks, it seemed ethereal, and no one could predict its future development, filled with various innovations, protocols, and products, with hardly any surviving a decade later. Technologies like search engine crawling algorithms, applications like news portals being just browser shells of newspapers, and concepts like how network effects influence social media may be important, but they are not the core logic of the internet. However, grasping the underlying logic that the internet "unprecedentedly reduced the cost of information flow" allows one to realize how it will radically change society and identify trends when search engines, social media, online shopping/payment, smartphones, ride-hailing, local services, and algorithmic recommendations emerge.

Technological progress is often cumulative rather than leapfrogging, making it extremely difficult to predict the future, especially in the current early stage of both policy and technology. Today's Web3 is still very early, and the vast majority of the products and services, business models, and token models we debate now will likely perish in the bubble burst. Therefore, this article does not discuss the circuit design of ZK-Rollup, whether GameFi is just a tokenomics shell game, or how composability affects DeFi, but rather focuses on the most core question: What are the innovations of Web3? How will it change the world?

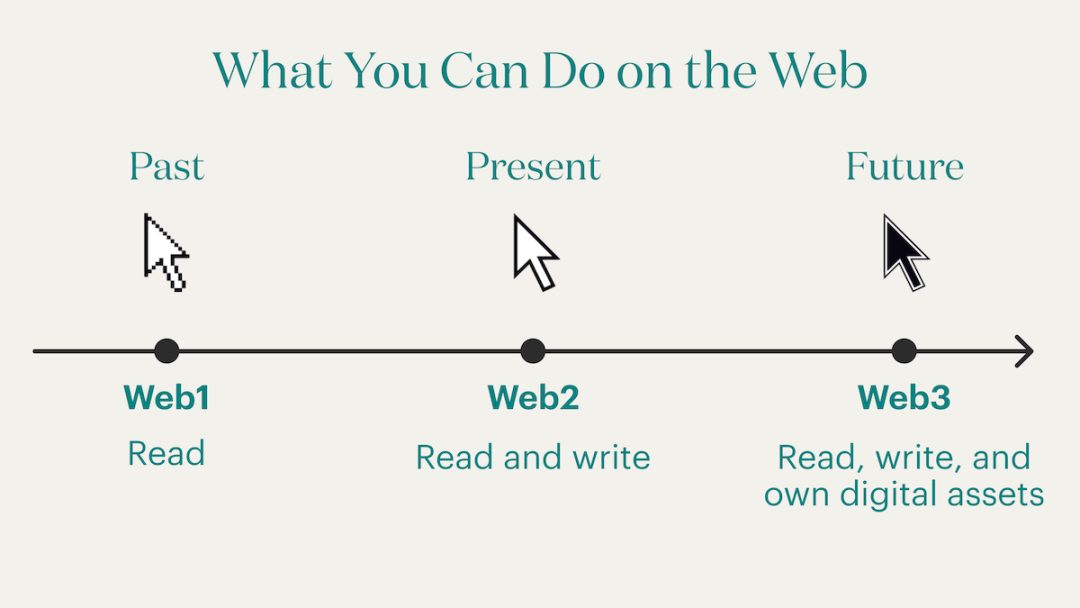

What is Web3

Web3 is a web system built on blockchain or digital asset-related technologies. Definitions are used to understand structures and mechanisms; this definition is sufficiently comprehensive but also confusing. The most widely accepted statement about Web3 is: "Web1 was read-only for most users, Web2 allowed users to read and write, and Web3 empowers users with the rights to read - write - own through blockchain."

However, the ability to read and write is an interaction between people and content, while ownership is essentially a social contract relationship. The former deals with information, while the latter deals with assets, and the dimensions they handle are different. Therefore, viewing Web3 merely as an extension of Web2 is a misaligned perspective. Why would people choose to use the energy-consuming, expensive, slow, and complex Web3 over the cheap and convenient Web2?

There is only one reason for an innovation to be adopted: it meets new needs or better satisfies old needs. Enduring complex mnemonic phrases, expensive transaction fees, occasionally crashing public chains, protocols that are regularly hacked as ATMs, and the risk of phishing sites draining wallets are not for the sake of redoing what can be done on a phone on the blockchain, at least not now. Otherwise, it is hard to explain why someone would spend millions on an ugly image that anyone can right-click and save.

Let’s return to the starting point, beginning with the titles of the white papers: Bitcoin, a peer-to-peer electronic cash system; Ethereum, a next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform. This article will explain that the core innovations of Web3 lie in the titles of the white papers: "Token" and "Smart Contract." It will also attempt to explain from the perspective of institutional economics that rather than being a technological innovation akin to the "steam engine," it is more similar to an institutional innovation of "capitalism."

Institutions and Institutional Economics

Institutional economics is a subset of economics that intersects with political science, sociology, or history, studying the role of institutions in socio-economic contexts using economic methods. An individual's ability to satisfy their desires is limited; no one on Earth has ever produced a pencil alone. This relies on the cooperation and contributions of countless unknown individuals, including Chilean graphite workers, Canadian lumberjacks, Taiwanese glue manufacturers, German assembly line manufacturers, Chinese merchants, and millions of others.

In a modern society characterized by intricate and specialized labor division, individuals need to transact and cooperate with countless strangers and organizations. Human interactions, especially in economic life, rely on trust. Trust is based on order, and to maintain this order, various rules prohibiting unforeseen behaviors and opportunistic actions are necessary; we call these rules "institutions."

Why does human society need institutions? The main reasons can be summarized as follows: limited human rationality (scarcity of subjective intellectual resources), uncertainty of the objective environment, and human opportunism. Institutions make human behavior predictable, reducing the costs of coordinating activities in large-scale human cooperation, thereby enabling effective resource utilization. The reason we can confidently hand over the money we earn through diligent work to a bank teller whose appearance we will forget in the next moment is that they are bound by institutions. Reflecting on this, many things in human society that we take for granted are actually suspended on a web of trust woven by institutions.

Institutions evolve and are not the same as policies. When people discover more effective and efficient institutions to replace existing ones, the possibility of institutional change arises. Institutions regulate relationships between individuals, and these relationships are a game of social relations where conflicting interests arise in almost all human activities. The ultimate goal of the relevant parties is to achieve a favorable outcome for themselves through their choices.

While economists treat economic processes as game processes, they view institutions not only as the rules of the game but also as the outcomes (equilibrium) of the game. As long as people repeatedly engage in transactions or other economic relationships, rules will emerge through gradual evolution or conscious design. When we look at history over a longer time frame, all events referred to as revolutions, reforms, restorations, progress, and regress fundamentally involve institutional evolution.

Compared to law, political science, ethics, cultural studies, sociology, and even anthropology, institutional economics focuses on different levels and perspectives regarding institutions. North defines institutions as the rules of the game in a society, which are various economic, social, political organizations or systems formed by people. They determine the framework within which all socio-economic activities and various economic relationships unfold, thus linking all social sciences intrinsically as a common category.

Institutions in human society are all-encompassing, from constitutions to social etiquette to the coordination of traffic lights, with vastly different importance and impact. Institutional economics is concerned with the creation and evolution of institutions that have the most far-reaching impact on human economies. Rational choices made by humans will create and change institutions such as property rights structures, laws, contracts, forms of government, and regulations, which will provide incentives or establish costs and benefits. Ultimately, these incentives or cost-benefit relationships will govern economic activities and economic growth over a certain period.

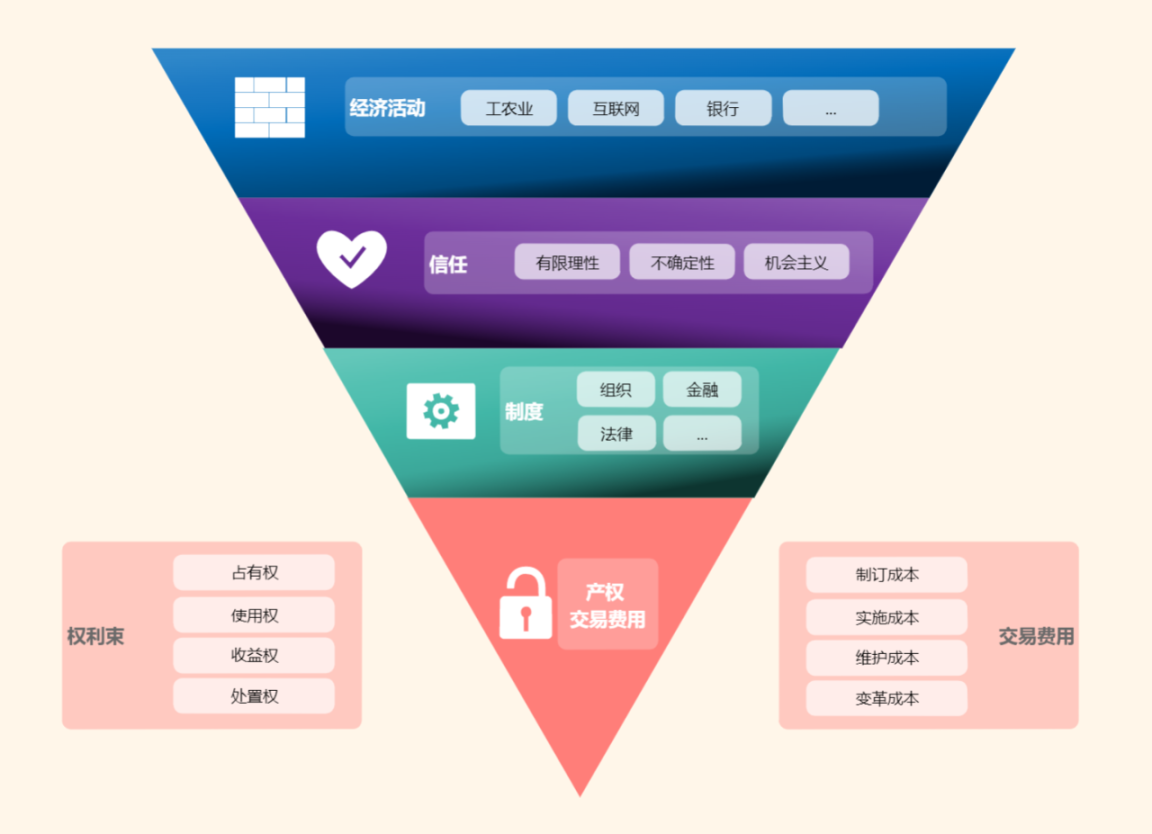

Transactions are the basic unit of human economic activity and the fundamental analytical unit of institutional economics. The basic theoretical tools of institutional economics are transaction cost theory and property rights theory.

- The transaction cost paradigm constitutes the theoretical framework of institutional economics. Without transaction costs, regardless of how production and exchange are arranged, the use of resources would be the same. Transaction costs fundamentally influence what is produced in the market, what types of exchanges occur, which organizations survive, and which rules of the game can persist;

- The premise of transactions is property rights; without property rights, transactions cannot be discussed. Transactions and exchanges are different; it is not about buying and selling goods but about buying and selling rights. The property rights system is the fundamental basis of economic operation; the type of property rights system determines the type of organization, technology, and efficiency.

There are differences between the property rights approach and the transaction cost approach. The former requires an analysis of individual incentives, while the latter places individuals within a broader institutional framework, such as allowing companies to be analyzed as organized corpses.

a. Property Rights

Property rights refer to the ownership or rights of property, emphasizing the ultimate control that the owner has over the property. Today, all commercial laws used by countries around the world are derived from Roman law, where the core concept of property rights is control. The simplest goods, like pencils, cannot separate rights from the goods themselves, while complex goods, such as land, forests, enterprises, knowledge, ideas, and financial products, require rights to control and enjoy them, which cannot be handled by simple transactions. The transaction of any goods or resources can only proceed smoothly when property rights are clearly defined, allowing the market price mechanism to function and resources to be effectively allocated.

Private property rights, collective property rights, and state property rights essentially cover the scope of property rights. Different types of resources require different forms of property rights to match. Property rights are both a relationship of interests and a relationship of responsibilities, corresponding to incentives and constraints. Well-defined property rights restrict how people use assets and incentivize them to maximize the value of those assets.

Property rights as control give rise to many other rights, known as bundles of rights. These include rights of possession, use, income, and disposal; the disposal right is further divided into transaction rights, inheritance rights, gift rights, etc. The divisibility of property rights can increase the utility of assets, allowing individuals with different needs and knowledge to put a unique asset to its most valuable use.

For example, individuals with entrepreneurial talent but without assets can more easily acquire others' assets to maximize total output for both parties; the massive capital required for major projects and infrastructure can be gathered through shareholding, and so on. From a developmental perspective, as the degree of socialization of production increases, the transition from unified to fragmented property rights is a specific manifestation of the development of social division of labor in terms of the exercise of property rights.

On the basis of property rights systems, other institutions emerge, such as corporate systems, market systems, financial systems, legal systems, and political systems. The intricate and complex structures of modern enterprises and financial markets are innovations based on property rights systems. In institutional change and innovation, property rights are an important variable. This point should be deeply felt by China, which has undergone market economic reforms.

b. Transaction Costs

Transaction costs are the operational costs of economic institutions, broadly including the costs of formulating, implementing, maintaining, and changing institutions. In reality, institutions, or the rules of transactions, vary widely, and each institution has its transaction costs. For example, the costs of the property rights system include the costs of measuring, defining, maintaining, and exchanging property rights.

Transaction costs are central to institutional economics, and transaction cost theory can be used to study various institutional arrangements throughout human history and in reality. In the perfectly competitive market of neoclassical economics, transaction costs are zero, private property rights are sound, and Adam Smith's "invisible hand" can achieve Pareto optimal resource allocation, making institutions, property rights, laws, norms, etc., optional. In the frictional reality of economic life, many institutions are either created to reduce costs or make previously impossible actions due to high transaction costs possible.

Measuring transaction costs is a key challenge in theory, including two parts: costs measurable through the market. According to some estimates, transaction costs in modern market economies account for 50%-60% of net national product, not including the initial costs of establishing new institutions and organizations; and hard-to-measure costs, such as acquiring information, waiting time, bribery, and losses caused by incomplete regulation and enforcement.

Specifically, transactions in real life are completed through contracts. A contract is a relationship of rights established by parties (two or more) during a transaction to improve their economic situation (at least rational expectations). Any transaction always occurs within a certain contractual relationship, whether explicit or implicit. Modern economics views all market transactions, whether long-term or short-term, explicit or implicit, as a contractual relationship. When a consumer purchases a train ticket, there is an implicit contract between the consumer and the railway company: the consumer pays a fee, and the railway company safely delivers the consumer to their destination within the specified time.

The basic function of a contract is to maintain cooperation among the contracting parties, encouraging them to seek new and greater benefits while adhering to commitments and responsibilities. It is precisely this nature of the contractual system that combines thousands of different and nuanced ownerships into a vast ownership; the same ownership can also be reasonably separated, allowing for division of labor and cooperation, forming different links in the chain of owners - operators - users. Throughout the long process of economic development, human transaction behaviors have continuously expanded and evolved, and contracts have become increasingly complex.

From the perspective of contracts, the transaction costs of specific transactions should include: the costs of preparing the contract (information gathering), the costs of reaching the contract (negotiation, signing), and the costs of supervising and enforcing the contract.

From Property Rights to Tokens

An efficient property rights system can transfer property rights from inefficient hands to efficient ones. Applying the earlier transaction cost theory, to achieve a more efficient property rights system, it is necessary to reduce the costs of measuring, defining, maintaining, and exchanging property rights:

- The completeness of property rights attributes; the more complete the property rights attributes, the more efficient the property rights system.

- Clear definition of property rights; this is a prerequisite for the effective functioning of market mechanisms.

- Effective protection of property rights; the better the protection of property rights, the better their functions are realized.

- Low transaction costs for property rights; this is the foundation for smooth transactions of property rights.

Each advancement in property rights systems is often linked to innovations in the above areas. The definition of intangible assets such as patents and copyrights allows knowledge owners to gain material benefits from sharing knowledge; the separation of ownership and management rights has led to the emergence of modern joint-stock companies; the higher the degree of rule of law and marketization in a country, the more efficient the market becomes. In contrast, the difficulty in defining ownership of air has led to market failures regarding pollution issues.

Tokens are the atomic units of Web3, managed collectively by distributed ledgers. Tokens originated from Bitcoin, marking humanity's first attempt to replace monetary systems with technology, but this has evidently failed, and Bitcoin has become a form of digital gold. Its failure was foreseeable because the monetary system is the most complex and fundamental institution in human economic activities. However, Bitcoin has opened a door to a new world for us: Tokens.

On public infrastructures like Ethereum, anyone can deploy Tokens at a very low cost. As of the time of writing (August 2022), CoinMarketCap lists over 9,000 publicly traded Tokens, and this is just the number of Fungible Tokens. These FTs can be subdivided into many categories, from securities to utilities to stores of value to governance, with different rights corresponding to various existing property rights in real life.

The multiple roles of Tokens are intricate; they can represent any form of economic value or access rights (on-chain versions): stocks, bonds, currencies, gift cards, points, club memberships, IDs, diplomas, flight tickets, etc. While it is common for emerging fields to lack clear definitions, this does not mean that the multiple roles of Tokens are erroneous; rather, it reflects their characteristic of representing value in the most abstract sense.

Anyone can use Tokens to issue any type of asset and access rights, including entirely new asset classes. Relating to the earlier concept of property rights, Tokens are a property management tool that can represent any existing digital or physical asset or access rights to others' assets. If you agree with the earlier discussion on the importance of property rights, it should not be difficult to understand the profound impact this will have.

But why must property management be Tokens? Why must it be placed on the blockchain? The digital assets in Alipay are also a form of property proof and are even more efficient. Merely inventing the concept is not enough; the implementation of the concept requires supporting applications. Compared to off-chain property rights, the core advantages of Tokens lie in: cryptographic property protection, competitive property innovation, and efficient property circulation. At the same time, the underlying property innovation is the cornerstone of complex economic activities, such as contract innovation (smart contracts) and organizational innovation (DAOs).

a. Cryptographic Property Protection

Only when there is a background for protecting property rights can people focus on efficiency and operational issues under the protection of property rights. The complex property mechanisms in modern society rely on state management for their underlying coordination. This is because the state has corresponding rules to organize its internal structure and has the coercive power to implement rules and compete with other states, giving it an advantage in "potential violence" compared to other organizations.

Violence is essentially a resource, including both tangible tools of violence like armies, police, and prisons, as well as intangible assets like authority, privilege, and monopoly rights. The term "violence" here carries no pejorative connotation; institutions evolve from mutual constraints among individuals, and the logic of current property protection is such that it is more efficient for the state to undertake this function. The reason state violence resources can be used more effectively is that they are violence against violence, and their function is to produce and sell (through taxation) a certain social product: safety and justice. If we were in a state of anarchy, everyone would have to resist others to protect their property, and state violence can achieve economies of scale and prevent "free-riding" problems.

However, the protective functions of government are limited. A significant portion of the government's protective functions is achieved through regulation. There is a tendency within the government's protective functions to emphasize security at the expense of cultivating the ability to coordinate and control competitive systems, thus sacrificing prosperity. Moreover, the globalization of information and capital has made cross-border transactions and cooperation increasingly frequent, and at this time, the protection of a single country is often inadequate, especially as geopolitical conflicts intensify, leading to even more fragmented trade.

Blockchain/Web3 is a new economic infrastructure used alongside the state for coordination and exchange. It uses cryptographic methods to protect the security of property rights, starting from fundamental property rights, shifting trust in complex institutions from individual organizations to decentralized nodes and verifiable code. It has unique economic characteristics that allow it to complement and, in some cases, compete directly with existing mechanisms.

b. Competitive Property Innovation

Due to the interconnectedness of property rights systems, historical changes in property rights have been relatively slow, but each advancement brings significant impact. The current on-chain economic system is largely disconnected from the real economy, and innovation is much more radical. Web3 ensures no barriers to entry, low thresholds, open-source, and competition through technological means, leading to a continuous emergence of basic Token innovations. "One day in the crypto world is like a year in the real world," originally referring to the volatility of Token prices compared to traditional assets, also indirectly indicates that in such an open competitive market, new standards, protocols, and products are generated and rapidly validated and eliminated by the market every day.

For example, in terms of property definition, NFTs that tokenize digital information assets cannot be freely exchanged before being tokenized. Although the current real applications are limited to seemingly trivial profile pictures and digital art, this is because the current ERC-721 standard has not truly opened the bundle of rights for digital information property, leading to a search for application scenarios that can only fall into the realm of a risk-free, tangible economy.

However, continuously updated new protocols, such as ERC-4907, which can separate ownership and usage rights of NFTs, and non-transferable SBTs, are constantly exploring real use cases and will be immediately subjected to market competition. Many outstanding talents are exploring how to use NFTs to create a fairer creator economy and more open games.

Another example is in terms of attribute definition, the composability of DeFi protocols. Combined with the automatic execution characteristics of smart contracts, new DeFi applications can safely connect to existing DeFi applications, effectively adding functions and rights to existing Tokens, allowing them to gain liquidity from other protocols and improve capital utilization efficiency.

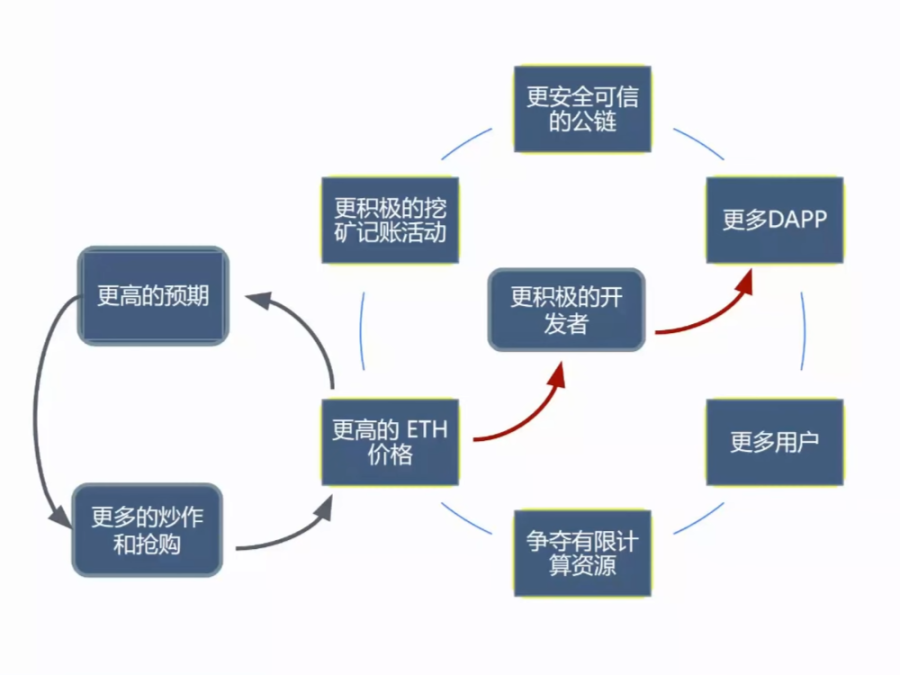

Additionally, in terms of business models, there are various dazzling Tokenomics designs. The same Token can split into a bundle of rights; holding ETH can pay gas fees, serve as the base currency for interacting with the Ethereum ecosystem, enjoy the appreciation of the Token price brought by the prosperity of the Ethereum ecosystem, and after the Merge, holders can also earn dividends through staking. Token holders are both customers and owners. This introduces business logic to property rights that were previously separated under traditional corporate structures, linking business flywheels and financial flywheels through Tokens, which can incentivize users in the early stages to accelerate reaching the critical point of network effects. Although some models have been criticized as Ponzi schemes or death spirals, the exploration of such business models is meaningful.

From Contracts to Smart Contracts

With property rights established, the next step is transactions. Smart contracts are essentially agreements guaranteed to be automatically executed by code. The name sounds impressive, but smart contracts are not truly intelligent and can be somewhat clumsy; a bug can lead to massive financial losses. Similar to replacing salespeople with vending machines and using AMMs instead of centralized exchanges, they can reduce transaction costs, trust costs, and human risks in the process, increasing asset circulation speed and accelerating price discovery.

Can algorithms really replace contracts? Returning to transaction cost theory, can algorithms reduce the costs of preparing contracts (information gathering), reaching contracts (negotiation, signing), and supervising and enforcing contracts? The ideal is appealing; simple transfers and over-collateralized lending can certainly be executed at the lowest cost using computers/code/machines/smart contracts, but economic activities between people are so complex that current smart contracts cannot effectively implement even the most basic credit lending contracts or employment contracts (the foundation of DAOs).

The calculative nature of smart contracts makes them more suitable for handling complete contracts. However, in real life, contracts involving human capital face relatively higher measurement costs than material capital, and most contracts are incomplete. In complete contract theory, the contract terms detail the rights and obligations of each party in different situations when unpredictable future events occur, the risk-sharing arrangements, the methods of enforcing the contract, and the ultimate outcomes achievable by the contract.

In incomplete contract theory, due to individuals' limited rationality, the complexity and uncertainty of the external environment, information asymmetry, and incompleteness, all parties involved in the contract and arbitrators know that the contract terms are incomplete. They also need to coordinate different incentive and constraint mechanisms to fill the gaps in the contract, correct distorted contract terms, and adapt more effectively to unexpected disruptions.

As the costs of measuring, defining, maintaining, and exchanging property rights continue to decrease, the incompleteness of contracts can be alleviated to some extent. In economic activities and contracts, there are many "calculative" components that we have previously simulated using human effort. However, with technological advancements, today’s computers, especially the development of blockchain smart contracts, are more aligned with the essence of calculation. In the contracts between depositors and banks, complex check verifications once required assistance from bank tellers, but as banking systems and bank cards have continuously reduced the costs of supervising contracts, ATMs have replaced bank tellers. Similarly, in employment contracts between employers and employees, the output of employees needs subjective evaluation from employers, but with the evolution of standardized assembly lines, piece-rate wages have replaced employer evaluations.

The superiority of machine/code contracts over human contracts lies in precision and efficiency. When property rights systems are sufficiently advanced, whether due to technological or institutional progress, computational systems can significantly reduce transaction costs and enhance precision, replacing humans as the dominant force in contracts. The trend can already be seen in the complex Meituan delivery scheduling system, which connects riders, merchants, and customers, involving the signing and execution of multiple complex contracts:

- Costs of preparing contracts: Merchants present product information on the platform for customers to choose.

- Costs of reaching contracts: Customers use online payments to sign contracts, riders select employment contracts from system allocations, and merchants accept orders to prepare products.

- Costs of supervising and enforcing contracts: Rider/merchant evaluation systems, with the system automatically calculating and settling the income of riders and merchants.

Contracts are the results of parties freely choosing without interference or coercion, including the freedom to sign or not sign, the freedom to choose contracting parties, the freedom to determine contract content, and the freedom to choose contract methods. Any third party, including the state as a legislator and judiciary, should respect the free consent of the parties involved. One of the major claims of Web3 is to overthrow the Web2 giants because, although they superficially provide the aforementioned freedoms, they effectively impose significant contracting costs. The creators of blockchain and smart contracts are the rule-makers and maintainers, who are not necessarily participants; the participants are strangers to each other. As more property rights are clarified and placed on-chain, imagine a delivery scheduling algorithm running on Web3 without Meituan's involvement, or a more broadly defined contractual system, where the formulation and maintenance of rules are made public and competitive, creating fairer and more efficient rules, reducing tragedies like "delivery riders being trapped in the system" due to the unchecked growth of platform power.

As property rights systems become more granular and refined, many components of economic activities, including repetitive mechanical parts in production and transactions, calculative rules, and order, may be replaced by machines and smart contracts. The developed property rights in the financial system, clear calculative rules, and high transaction costs make it easier to transform and create significant economic benefits, explaining why DeFi is the first explosive application direction of Web3.

The Future of Web3

Following the logical chain, in the future, we may engage in off-chain interactions and production, while the formulation, execution, and supervision of contracts related to economic activities occur on-chain, greatly reducing transaction friction and improving resource allocation efficiency. It sounds somewhat cyberpunk; envisioning the future is always pleasant, but it is evident that the current Web3 is far from the ideal described above; it is still in a chaotic state. Unlike the information attributes of the internet, due to its inherent economic attributes, a swarm of gamblers and fraudsters have rushed in, and due to its profound revolutionary significance, idealistic dreamers are eager to preach.

Progress cannot rely solely on realists who only speak of reality or idealists who only have ideals; it requires idealistic realists and realistic idealists. Vitalik is the latter type of person; we all know the unsatisfactory phenomena, but the key is to solve problems. We still have a lot of work to do, which also means there are many business opportunities:

- Innovations in cryptographic technology, such as better consensus algorithms, privacy protection, virtual machines, programming languages, sharding, zero-knowledge proofs, decentralized storage, etc.;

- Enhancing user experience, such as better developer tools, easy-to-use wallets, low transaction fees, and stringent asset security guarantees;

- Connecting with reality, such as more accurate and decentralized oracles, simpler fiat Token conversions, more ownership of physical assets, on-chain operation of real contracts, DID, SBT, etc.;

- Regulatory intervention, which, even if it can compete with existing systems in the long term, is a necessary path for short-term integration;

- …

As for applications, what other rights can be represented by Tokens? How should transaction rules be designed to reduce the transaction costs of Tokens? How can ordinary users without programming backgrounds easily create their own smart contracts? How should organizations based on property rights and contracts evolve? The road ahead is long and winding, and there are many innovations worth exploring.

Conclusion

In the context of economic development, "technological determinism" and "institutional determinism" are two representative viewpoints. Neoclassical theory posits that economic growth is primarily constrained by factor inputs and technological progress, with institutions merely adjusting passively or lagging behind; while institutional economists argue that the fundamental factor is institutional progress, as efficient economic organizations and appropriate incentive arrangements lead to the rise of the Western world and the outbreak of the Industrial Revolution.

It is challenging to completely separate institutions from technology; their relationship is actually intertwined. The so-called determinism of the two must ultimately be linked to costs, and their performance in the development of socio-economics can be analyzed through costs. Viewing innovation as a system, technological innovation and institutional innovation are two indispensable components that must be combined to be complementary and interactive.

Although the internet is primarily an innovation of information technology, it has also brought about flatter and borderless organizational forms. While this article has been framed from the perspective of institutions to think about the logic of Web3, technological progress is also quite important. Furthermore, due to space limitations, a more in-depth analysis of more complex institutions such as organizations, cooperation, enterprises, and even national theories will be explored in future opportunities. The author is not a professional scholar of institutional economics but aims to provide a new perspective on thinking about Web3, and welcomes discussions.