a16z: How should the Web3 governance reward system be designed?

Original Author: Eliza Oak, a16z

Compiled by: Karen, Foresight News

A core challenge of democratizing online governance systems is how to incentivize long-term citizen participation through rewards.

Current Web3 governance systems often use transferable tokens, but these tokens have some obvious limitations (e.g., tendencies toward oligarchic dominance, lower resistance to Sybil attacks, and incentives for holders to sell tokens and exit), which can be overcome by moving beyond token voting.

In this article, I compare reputation-based and token-based participatory governance reward systems, outline the considerations for each type of governance reward system, and discuss how these rewards can be obtained and what power they may translate into.

Precedents for Rewarding Contributions

Political Influence is Often Based on Wealth, Not Merit

Historically, social and political influence has largely been based on wealth rather than merit. For example, in ancient Rome, the status of the Senate was distinguished by birth and land ownership.

During the Renaissance, wealthy families like the Medici bankers in Florence used their wealth to influence political and religious affairs as well as cultural movements.

Even in many modern liberal representative democracies, wealthy individuals and corporations influence political affairs through donations and lobbying. Other social systems explicitly designed to reward merit, such as university admissions, often reward wealthy and connected individuals through legacy admissions or alumni donations.

If Web3 aims to move toward a truly democratic online system, the question becomes how to prevent the re-creation of wealth-based hierarchies. How can we prioritize merit, value, and contribution over wealth and connections?

Performance-Based Reputation Systems are Difficult to Scale Beyond Niche Environments

Reputation is a way for society to attempt to capture merit.

For centuries, we have sought ways to collect and aggregate signals to discern who is trustworthy, capable, or deserving of recognition, thereby determining how to translate these signals into social status, access, and decision-making power.

For example, medieval European guilds certified the craftsmanship of artisans; reputation was held in tight-knit tribal communities; academic accreditation from universities; and credit ratings were used to assess someone's likelihood of defaulting on financial obligations.

Moreover, in today's digital environment, technology platforms have explored some reputation identification methods based on observed behavior rather than wealth. For instance, Google's PageRank algorithm, Reddit's reputation scores, and peer reviews on Amazon and Yelp. However, these systems often have less connection to wealth and relationships but tend to be limited to specific contexts and do not generalize to broader domains. Additionally, they are also susceptible to fraud and abuse.

Of course, large-scale reward systems are not without significant social risks. The key is to balance the power of technology with the goals of decentralized design.

Web3 Provides Possibilities for Merit-Based Online Governance

For the first time in history, Web3 enables us to design and implement highly credible, scalable reward systems.

For example, the immutability of blockchain ensures that rewards are tamper-proof and securely recorded, while smart contracts can transparently automate the implementation of rewards, reducing the need for intermediaries.

The representative compensation system of MakerDAO is one example of exploring reward systems in Web3, and I will discuss other examples later in this article.

These reward systems are based on new mechanisms for building trust and distributing rewards, which could be designed according to the participation of a broad user base to democratize the governance processes of entire technology platforms or other online communities.

Two Core Challenges in Designing Reward Structures

Two important questions in designing reward systems are:

- What should be rewarded?

- Who receives the rewards?

What Should Be Rewarded?

Models such as university capabilities, skill certifications, or credit scores are rough proxies for trustworthiness, contribution, and skill value. The key to determining what to reward lies in whether it genuinely reflects reputation.

For instance, in online governance, users might earn reputation scores for actions such as voting, attending town halls, or submitting governance proposals. So, aside from recording the frequency (quantity) of these actions, is there a way to assess the effort and value (quality) of these actions?

Who Receives the Rewards?

The core of determining who receives rewards is aggregation, where the tricky part is creating a standardized method and explaining it in a common language.

In terms of reputation, metrics are often context-specific: for example, credit scores reflect financial trustworthiness, driving records measure driving responsibility, and online assessments gauge restaurant cooking skills.

These metrics are not interchangeable; for instance, an excellent credit score does not guarantee someone's cooking ability. However, in online communities using reputation-based governance, incorporating a more inclusive view of reputation may be meaningful.

So how should we weigh these different components of reputation, and how can we adapt them to a broader social context? Should the design of reputation include everything in someone's crypto wallet, including finances, identity, and even virtual art and property?

Reputation Systems vs. Token-Based Systems

Token-based rewards are transferable, while reputation-based rewards are non-transferable. People may wonder which one should be used and why.

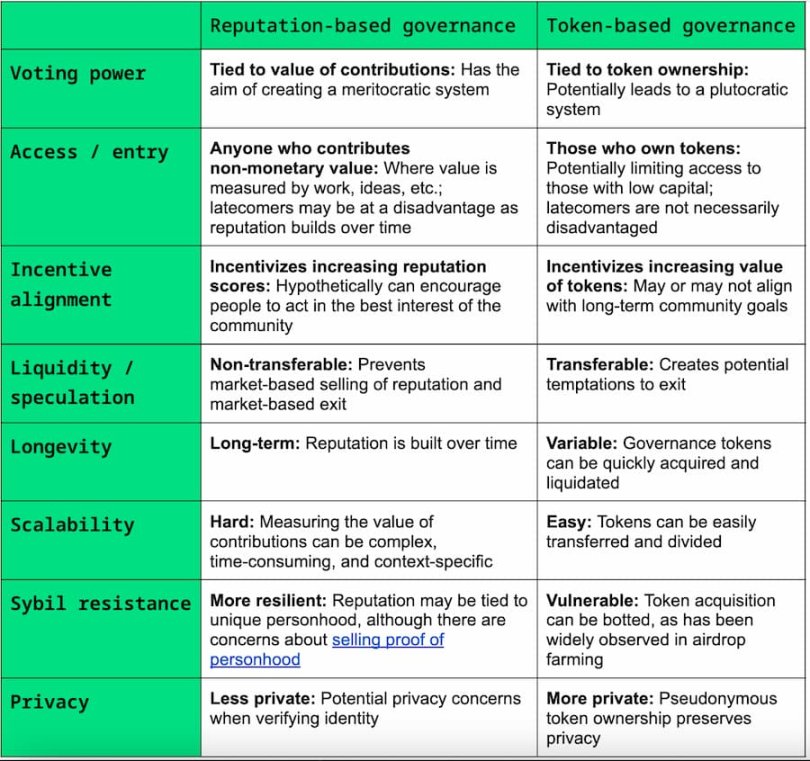

Early experiments in Web3 governance were often token-based, but there is currently a tendency to adopt more reputation-based systems as the default because, if successfully implemented, they would have clear advantages (summarized in the table below).

Overall, reputation-based governance may be reasonable for prioritizing long-term community cohesion, while token-based governance may be better suited for projects prioritizing scalability and liquidity. Weighing the access/participation dimension, reputation-based systems may lean toward early community members who can start building reputation sooner, although token-based systems are more suitable for wealthy individuals. In terms of resisting Sybil attacks, reputation-based systems aim to overcome the inherent Sybil vulnerabilities in token-based systems by associating reputation with identity (e.g., the Beanstalk hack). However, this may raise privacy concerns, depending on the methods used to verify identity, although these concerns can be mitigated through zk-SNARKs or other types of zero-knowledge proofs.

In practice, a combination of tokens and reputation scores may be a reasonable approach. Optimism's "bicameral" system, which consists of a reputation-based Citizens' House and a token-based Token House, is one implementation of this, but there is significant design space. Previous research has suggested that reputation systems should rely on a pair of tokens, one for representing reputation and the other for providing liquidity. Other projects are exploring dual governance models where staked token holders have veto power over governance token holders. For Lido, both LDO and stETH tokens are transferable, although it is conceivable to build non-transferable reputation-based governance tokens into a similar dual-token model.

Token-Based Systems

"Token-based governance" refers to a system where incentives or rewards are associated with the ownership or acquisition of fungible tokens. For example, Uniswap's UNI token can be used to vote in Uniswap governance.

Compared to reputation-based systems, the transferability of these tokens allows new participants to engage more easily in protocol governance, although these systems may potentially lead to oligarchic dominance, where those with more capital exert greater influence. Token holders have a direct financial interest in the success of the project, incentivizing them to vote in ways that promote their long-term financial value.

Unfortunately, the financial interests of token holders do not always align with the long-term non-financial interests of the community. Examples of these types of tokens include Ethereum ERC-20 tokens, Cosmos ICS-20 tokens, and Solana SPL tokens.

Currently, most projects use a "one token, one vote" model for decision-making regarding the project. For instance, in MakerDAO, MKR token holders can vote on protocol changes to support risk parameters for DAI stablecoin collateral. In the decentralized lending protocol Aave, AAVE token holders can vote on which projects should receive funding from the Aave ecosystem reserves. In the decentralized exchange Uniswap, UNI token holders voted on changes to the fee structure of UNI tokens, affecting how trading fees are distributed between liquidity providers and token holders.

In token-based systems, some examples of implemented reward mechanisms for distributing transferable tokens include:

- Airdrops: Tokens are distributed to wallets at discrete points in time based on specific eligibility criteria. Airdrops are often used to incentivize certain behaviors, promote new projects, or distribute ownership more broadly within the community. DeFi protocols (e.g., Uniswap), Layer 2 solutions (e.g., Optimism), blockchain identity solutions (e.g., ENS), and even NFT projects (e.g., Yuga Labs' Bored Ape Yacht Club) have all experimented with airdrop rewards.

- Retroactive Rewards: Optimism has implemented multiple rounds of retroactive rewards to distribute tokens, sending OP tokens to users whose contributions supported the development and adoption of Optimism's public goods for a broader OP Stack ecosystem. Examples of public goods include adding code to the developer ecosystem, contributions to user experience and adoption, or active participation in Optimism's governance. Winners are selected through community nominations and voting in the Optimism Citizen's House.

- Liquidity Mining: Users earn token rewards by providing liquidity to decentralized exchanges or liquidity pools. Decentralized lending protocols like Compound Finance and derivatives liquidity protocols like Synthetix are examples of protocols that issue token rewards through liquidity mining. Unlike airdrops that distribute tokens at discrete times or in multiple rounds, liquidity mining sends continuous tokens to users for lending. This is similar to anonymous mining in Tornado Cash, where users earn token rewards by depositing tokens into an anonymous pool.

- Voting Escrow: To participate in governance, users must lock their tokens in a voting escrow. Users can increase their voting power by locking tokens for a longer period. For example, the DeFi exchange Curve Finance uses veCRV (voting escrowed CRV tokens) for voting escrow. In Curve, the longer veCRV is locked, the greater the boost in voting power, in addition to increasing voting rights. This can also serve as a defense mechanism against governance attacks based on flash loans.

Reputation-Based Systems

Reputation is earned rather than bought. While reputation can also take the form of tokens, its implementation differs from fungible tokens that can be bought or sold on the open market. In practice, reputation most commonly utilizes non-fungible tokens (NFTs), such as ERC-5114 (soulbound badges) tokens on Ethereum. Badges from the Optimism Citizen's House and Polygon's proposed reputation-based voting through Polygon ID are current examples of identity-based governance systems. Reputation-based governance can function in various ways in practice, including peer attestations, automated scoring based on observable behavior, or centralized selection (which I outline the trade-offs between different reward mechanisms later in this article).

Assuming reputation tokens could take the form of non-transferable fungible tokens (e.g., if the transfer function in an ERC-20 contract were disabled), people might use non-transferable fungible tokens to rate the contributions of community members in a more granular way.

These reputation-based governance systems can distribute influence more equitably and may provide better resistance to witch hunts. However, reputation-based systems do face inherent challenges, such as scalability and the subjective measurement of contributions.

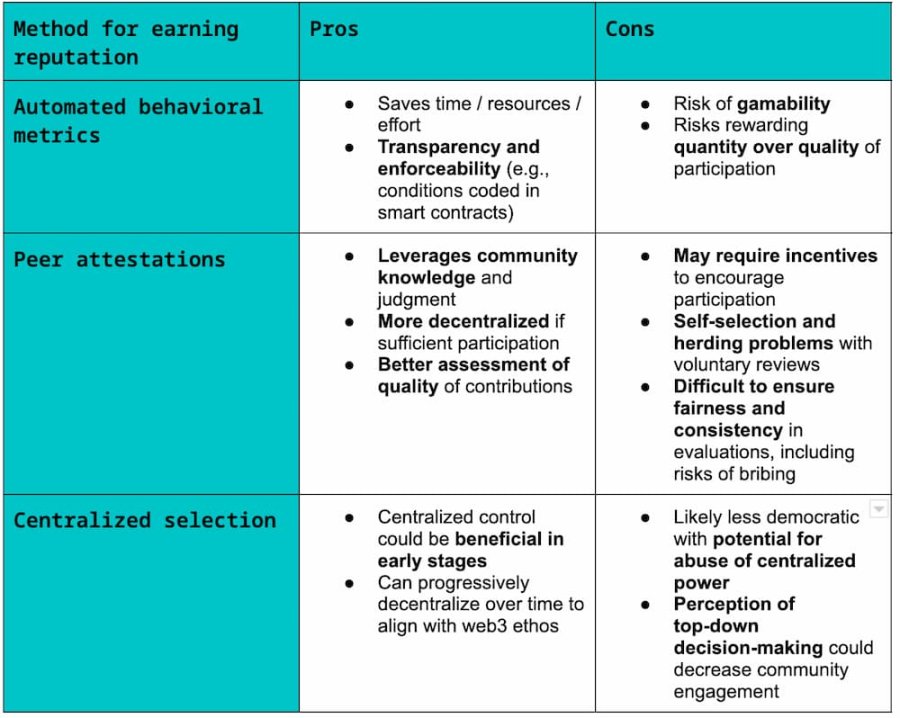

Reputation-based governance rewards are still in the early stages of implementation. Some examples of potential methods for earning reputation include:

- Automated Behavior Metrics: Reputation is automatically calculated based on users' observable actions within the system. For example, if a person attends a civic assembly, their reputation score might earn one point, while voting might earn five points. Such behavioral metrics could be hard-coded into smart contracts.

- Peer Attestations: Reputation is established through recognition or evaluation by other participants. This approach leverages peer evaluation to go beyond observable behavior, which may better assess the quality of participation but requires incentivizing people to take the time to rate their peers. A key challenge here is preventing bribery or other forms of reputation buying. An example of peer attestations in practice is Boys Club DAO's collaboration with Govrn, allowing members to record DAO contributions that can be attested by other community members and ultimately converted into retroactive rewards. Another example is proof of contribution to enhance governance accessibility, as proposed in the Optimism governance forum, which might use something like Ethereum Attestation Service (EAS) to create, verify, and revoke attestations.

- Centralized Selection: In the early stages of a project, a dedicated team manually selects individuals and assigns them high reputation scores based on established criteria. As the system matures, decentralization can gradually be achieved, allowing a broader community to play a larger role in refining reputation standards. This approach aims to balance quality assurance in the initial phase with the ultimate goal of fully decentralized governance. Vitalik Buterin mentioned this model in an August 2021 blog post, noting that "the simplest solution might be to start the system by manually selecting 10-100 early contributors, and then determining the participation standards for the N+1 round based on the selected participants of round N, gradually achieving decentralization."

Since reputation systems are not simply purchased on the open market, there is significant room for designing how to earn reputation rewards. The table below summarizes the pros and cons of different ways ecosystem participants can earn reputation:

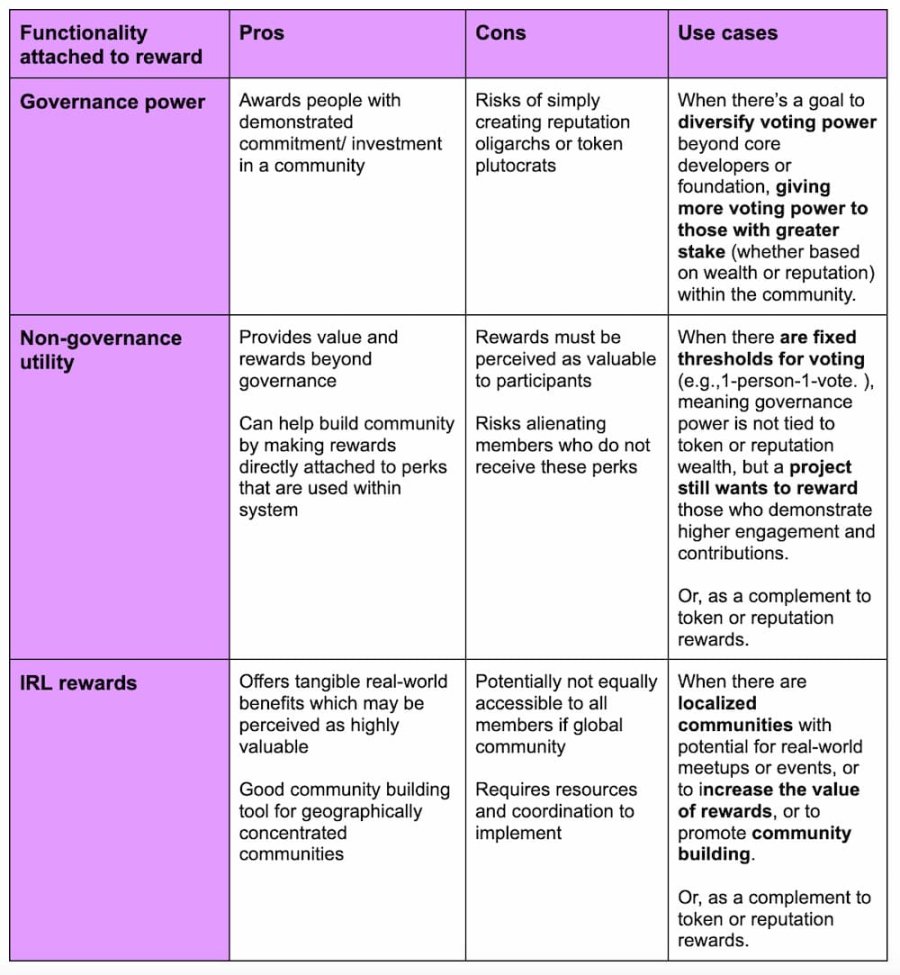

What Powers Do Rewards Have?

In addition to determining how to allocate rewards, a key question is to ascertain the value, access, privileges, or influence that rewards bring. Currently, most Web3 governance systems use transferable tokens that can be converted into voting power, where one token equals one vote.

Different types of value can be associated with rewards. Whether rewards are transferable (token-based systems) or non-transferable (reputation-based systems) will also affect the implications of these decisions, but at a higher level, these powers can be combined with transferable or non-transferable reputation.

What Forms Do Rewards Take?

- Governance Power: Rewards directly translate into the ability to vote, delegate, serve as a representative, publish proposals, or perform other governance functions.

- Non-Governance Utility: Rewards directly translate into non-governance utility within the online system. For example, this may include special access to community groups and events, priority access to staking, special avatars, or community status symbols.

- IRL Rewards: Rewards directly translate into IRL (real-life) benefits, such as attending official events with community members (e.g., parties, workshops, webinars), physical giveaways, or other non-digital consumer goods.

Successful reward structures are likely to involve a mix-and-match mechanism based on the nature and goals of the project, with governance rewards potentially corresponding to different combinations of governance power, non-governance utility, or real-life benefits.

Trade-offs to Consider When Designing Online Governance Reward Systems

To recap, various factors need to be weighed when designing online governance reward systems. The project's answers to these questions will influence whether its reward system should be adjusted based on reputation or tokens.

- How will information be collected and aggregated into rewards?

- How will rewards translate, aiming for interoperability of rewards (e.g., reputation scores) across different ecosystems (e.g., cross-chain interactions)?

- Will the rewards be designed by intermediaries or primarily based on decentralized interactions?

- Is there a desire to link rewards to real-world identities or anonymous accounts?

- Is resistance to witch hunts critical for the project and reward mechanism?

- Is there a plan to combine reputation tokens with transferable tokens?

Whether a project uses token-based governance depends on whether it is civic-oriented or economically oriented. As I outlined earlier, there are trade-offs on specific dimensions (e.g., scalability, access, privacy, Byzantine resistance, etc.). While some advocate for token voting (e.g., participation benefits), a common concern with token-based governance systems is the potential issue of oligarchy, where wealthy participants exert disproportionate influence, which clearly contradicts the ethos of Web3.

Reputation systems aim to link governance or other powers to the reputation individuals earn within the community. However, non-transferable reputation systems are challenging to implement due to the complexities of measuring and verifying reputation.

Therefore, exploring reputation-based governance and other ways to move beyond transferable token voting is an open and potentially fruitful area for decentralized governance.

I have outlined some considerations regarding the implementation of reputation systems, but this is an evolving field, and I look forward to further discussions and experiments to design effective online democratic governance systems.