The Fed's biggest nightmare has arrived: other factors that are getting closer to a shift

Author: David, W3.Hitchhiker

Note: Since September, geopolitical and financial market risks have unfolded one after another, leading global markets into increasingly unknown territories under the guidance of the Federal Reserve's super hawkish policies. By analyzing the latest trends in three local markets, we may be getting closer to a shift by the Fed.

1. U.S. Treasury Liquidity Tightens to March 2020 Levels

At the beginning of October, the liquidity issues in the U.S. Treasury market reached a new stage: Bloomberg's measure of Treasury liquidity indicates that the level of market liquidity tightness has returned to the levels seen in March 2020.

In March 2020, when the U.S. Treasury market collapsed due to panic selling, the Federal Reserve intervened as the buyer of last resort. The current liquidity levels may indicate that the Fed is ready to intervene in bond purchases at any time—even as it is currently engaged in so-called quantitative tightening.

New York Federal Reserve Bank Vice President Duffy stated, "The U.S. Treasury market is the most important securities market in the world and is the lifeblood of our nation's economic security. You can't just say, 'We hope it gets better'; you have to take action to make it better."

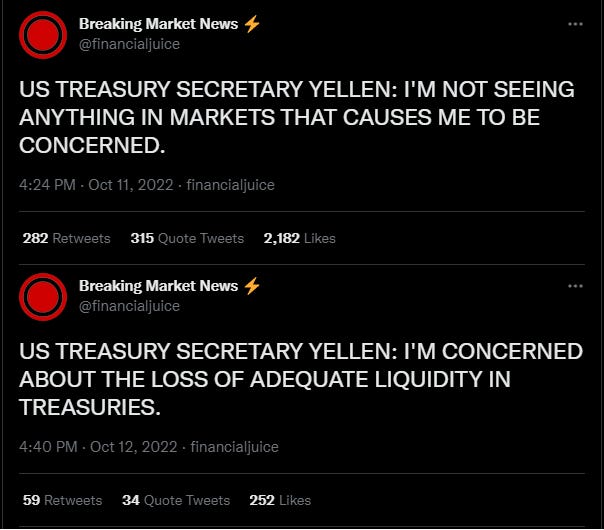

On October 11, the U.S. Treasury Secretary stated that she did not see any concerning situations in the financial markets. A day later, she reversed her statement, saying, "The insufficient liquidity in the Treasury market is concerning."

2. Fed's Earnings Turn Negative

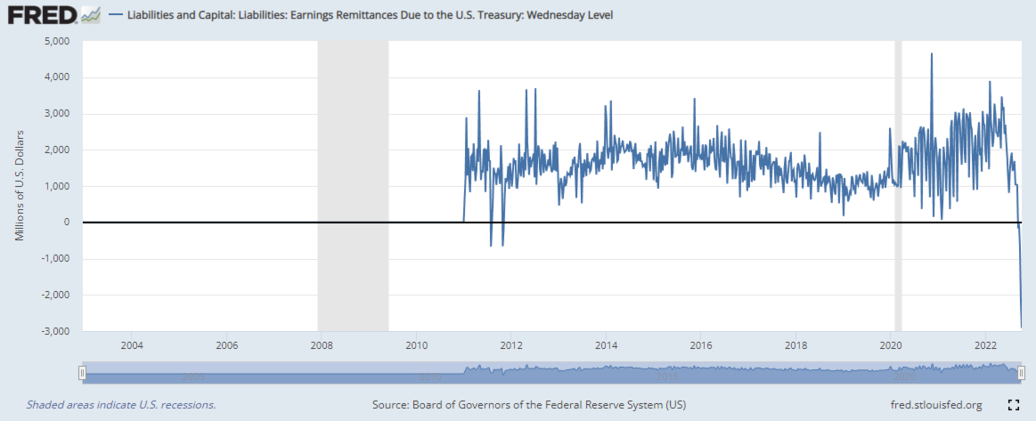

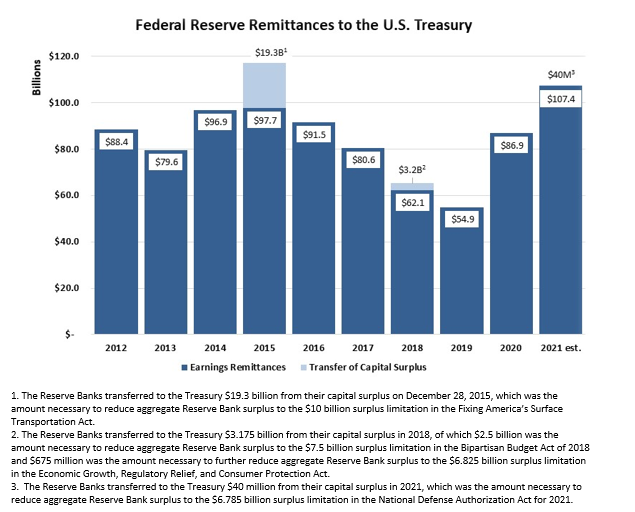

After multiple interest rate hikes, the Fed's interest expenses have exceeded the interest income generated from its QE-held bond portfolio.

Over the past decade, the Fed's income has generally been around $100 billion, which has been directly transferred to the U.S. Treasury. Estimates suggest that this year's losses due to interest rate hikes could reach as high as $300 billion (last year's U.S. military spending was around $800 billion). At the same time, due to QT, bond prices have plummeted, causing the Fed to potentially have to accept prices much lower than the purchase price when selling bonds, resulting in unrealized losses (non-cash items).

The Fed will not go bankrupt; faced with a massive hole, it can either completely ignore it or restart money printing.

In summary, higher interest rates will only increase cash consumption within the Fed and the Treasury. They will soon realize they are completely trapped. If they cannot effectively bankrupt themselves, they will not be able to tame inflation. Of course, central banks do not go bankrupt—on the contrary, they may pivot amid the storm of interest rate hikes and inflation.

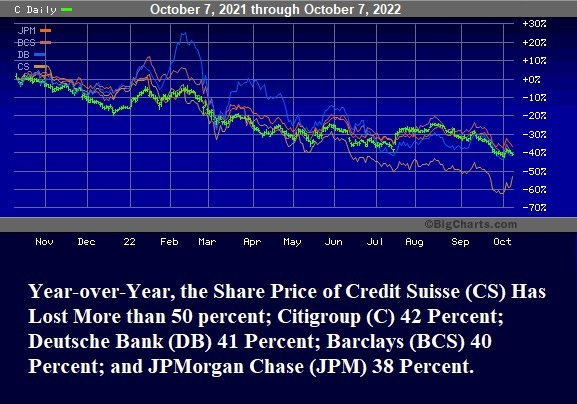

3. "Lehman Moment 2.0" Approaches

Recently, the market has been turbulent, with Credit Suisse and UK pensions facing dangers.

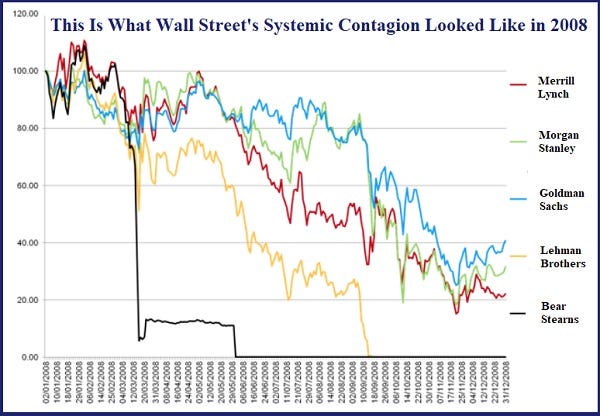

During the 2008 financial crisis, the transmission of inter-institutional risks was similar to the diagram below:

So, is there a possibility of a new banking crisis occurring after the 2008 financial crisis?

Before the National Day, several news media questioned whether Credit Suisse signaled another "Lehman Moment." The "Lehman Moment" refers to the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, a former Wall Street investment bank with a 158-year history, on September 15, 2008, during the expanding financial crisis on Wall Street. Lehman Brothers was the only major Wall Street bank allowed to go bankrupt by the Federal Reserve.

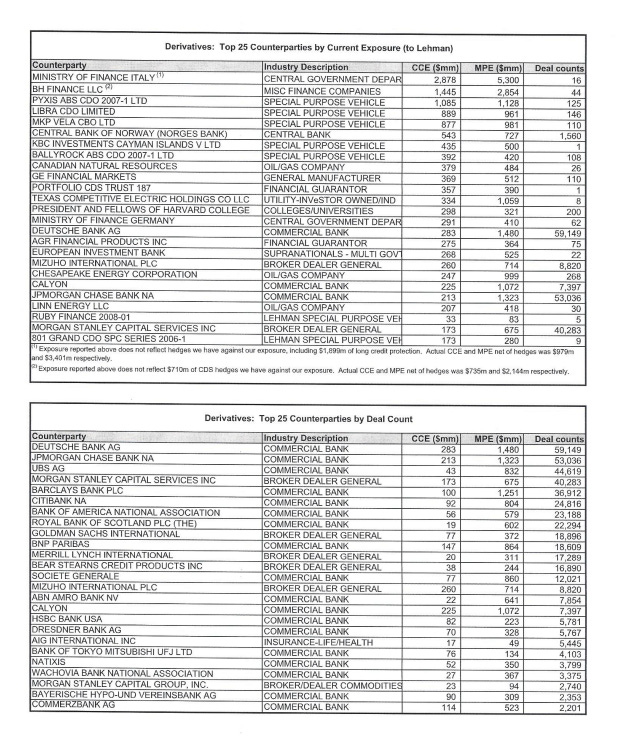

According to documents from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, at the time of Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy, it had over 900,000 outstanding derivative contracts and used the largest banks on Wall Street as counterparties for many of those trades. Data shows that Lehman had over 53,000 derivative contracts with JPMorgan; over 40,000 with Morgan Stanley; over 24,000 with Citigroup; over 23,000 with Bank of America; and nearly 19,000 with Goldman Sachs.

According to the conclusive report on the crisis analysis issued by the agency, the 2008 financial crisis was primarily caused by the following reasons:

"Over-the-counter derivatives contributed to this crisis in three significant ways. First, a type of derivative—credit default swaps (CDS)—drove the development of mortgage securitization. CDS were sold to investors to protect against defaults or declines in value of mortgage-related securities backed by risky loans…

"Second, CDS were crucial for the creation of synthetic CDOs. These synthetic CDOs merely bet on the performance of real securities related to mortgages. They expanded the losses caused by the bursting of the real estate bubble by allowing multiple bets on the same security and helped spread them throughout the financial system…

"Finally, when the real estate bubble burst and the crisis ensued, derivatives were at the center of the storm. AIG was not required to set aside capital reserves as a buffer for the protection it sold, but received a bailout when it could not meet its obligations. Fearing that AIG's collapse would trigger a chain of losses throughout the global financial system, the government ultimately committed over $180 billion. Additionally, there were millions of various types of derivative contracts between systemically important financial institutions—hidden and unknown in this unregulated market—adding uncertainty and exacerbating panic, contributing to the government's decision to provide assistance to these institutions."

Fifteen years after the crisis, do we see similar systemic financial risks?

In a working paper analyzing how banks choose counterparties in the over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives market published by the OFR (OFFICE OF FINANCIAL RESEARCH) on September 29, the authors found that banks are more likely to choose non-bank counterparties that are already closely connected to other banks and exposed to higher risks from other banks, leading to connections to denser networks. Furthermore, banks do not hedge these risks but instead increase risk by selling rather than buying CDS with these counterparties. Finally, the authors found that despite increased regulatory scrutiny after the 2008 financial crisis, common counterparty risk exposures remain correlated with systemic risk measures.

In simple terms, once a systemically important bank encounters problems, the financial system could still experience a systemic chain reaction like in 2008.

So, does the Fed need to pivot like the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England?

We shall see.