Why do trading platforms always experience liquidity issues?

Author: BlockBeats

As the overall cryptocurrency market enters a bear phase, many institutions, especially trading platforms, have faced a series of collapses and runs on the bank. The dramatic collapse of FTX this month has once again sounded the alarm, leading people to wonder why well-known trading platforms continue to fail in every cycle. Is this an inherent flaw of cryptocurrencies, or is it a systemic issue within the industry?

The Business Model of Trading Platforms

To answer this question, it is necessary to review the traditional financial asset exchanges that have developed over hundreds of years.

What is the business model of traditional trading platforms?

The main profit model of these traditional asset exchanges is quite similar, whether you are a stock exchange (like NASDAQ or the Shanghai Stock Exchange) or a commodity futures exchange (like the Chicago Exchange or the Dalian Commodity Exchange). Their primary revenue comes from transaction fees charged during trading.

Transaction fees can come from spot trading or from derivatives (such as perpetual contracts and futures), but the core principle remains the same: the more customers trade and the higher the trading frequency, the higher the exchange's fee income. After deducting labor costs and various expenses incurred from asset custody, the remaining amount is the profit of the trading platform.

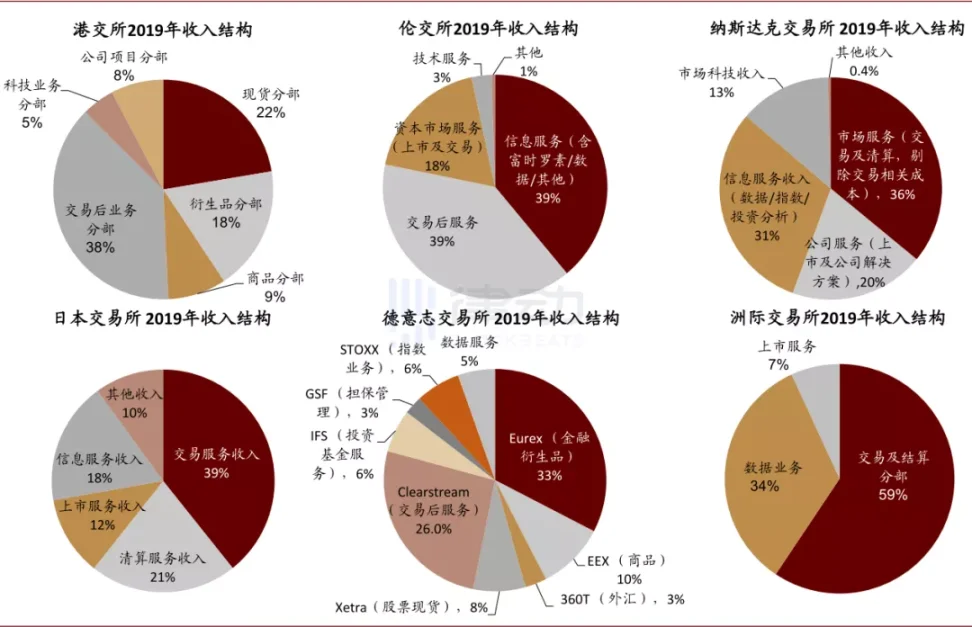

A casual search of the revenue composition of some traditional exchanges shows that their main income sources still come from traditional trading fees and value-added services like information services. In contrast, the fee income of the pure cryptocurrency trading platform Coinbase is even higher; based on the full-year data for 2021, Coinbase's fee income accounted for over 90%.

Source: Company announcements, company website, CICC Research Department

It can be seen that asset trading platforms operating under this model are not as attractive as people might imagine. While profitability may not be difficult, it is equally challenging to achieve exorbitant profits simply by opening a trading exchange.

The Business Model of Cryptocurrency Trading Platforms

Returning to the cryptocurrency trading platforms we are familiar with, the reason they often give the impression of being wealthy is that most of them do not adhere to the most basic trading exchange business model. They often engage in the misappropriation of user assets for speculation or market manipulation. This is the fundamental difference between these platforms and traditional compliant exchanges (like NASDAQ or the Hong Kong Stock Exchange).

So the next question is, how do these cryptocurrency trading platforms misappropriate customer funds?

Two Forms of Misappropriation of Customer Funds

Depending on the specific method, there are mainly two forms of misappropriation of customer funds by trading platforms: the first is straightforward and literal misappropriation, while the second is more covert.

Type One Misappropriation: Direct Transfer

For example, after the FTX incident, it was discovered that user custody assets that should have been stored in cold wallets were borrowed for speculative trading or to cover losses by Alameda, which is also controlled by SBF.

This type of misappropriation is akin to lending out customer custody assets, turning the customers' assets into IOUs for Alameda. If Alameda can continue to make profits and repay in a timely manner, it might be fine. However, if Alameda fails to invest and loses its ability to repay, the value of that IOU will drop to zero, resulting in users being unable to redeem their assets.

Type Two Misappropriation: Using Customer Assets for Trading

The second type of misappropriation is more covert than the first because, theoretically, these assets still remain in the exchange's accounts or addresses. Moreover, many times, the total asset value of the trading platform may exceed the value of its liabilities (i.e., the value of user deposits), which is why many platforms repeatedly claim they have sufficient reserves.

So, if that's the case, why do we still refer to using customer assets for trading as "misappropriation"?

Let's consider a simple example: suppose a trading platform only has $10 million in Bitcoin in customer custody (this $10 million forms the platform's liability to customers, who can withdraw it at any time). For speculative purposes, the platform exchanges $5 million of this for Shib, which has greater appreciation potential.

In a bull market, the price of Shib purchased by the platform triples to $15 million. Assuming the price of Bitcoin remains unchanged, the platform now holds $15 million in Shib and $5 million in Bitcoin, totaling $20 million in assets. Meanwhile, the liability to customers remains $10 million in Bitcoin. Clearly, any audit report issued at this time would show that the platform's user assets are fully redeemable.

However, if the market turns bearish, and the price of Bitcoin drops by 50%, while Shib drops to zero, the platform's assets would then be $2.5 million (50% of $5 million) in Bitcoin and $150,000 (1% of $15 million) in Shib, totaling $2.65 million. But the liabilities still amount to $5 million in Bitcoin. At this point, the platform's assets are clearly insufficient to cover its liabilities to users.

Note that the assets in the platform are still stored in the platform's addresses or accounts, and there is no occurrence of the first type of misappropriation. However, users' assets have still suffered losses.

This is one reason why platforms are more prone to collapse when the market turns bearish: the assets they hold, due to the platform's own speculative trading, lead to a mismatch in risk exposure compared to the assets deposited by customers. Even if previous audit reports indicated that the platform was over-reserved and there was no occurrence of the first type of misappropriation, as market prices fluctuate, the platform may still face insolvency issues, ultimately leading to a run on the bank.

We can also see signs of the second type of misappropriation in the collapse of FTX. According to certain rumors, FTX's assets were still far above its liabilities to users at the beginning of this year, with major positions in FTT, Sol, and other FTX-related tokens. However, as the market declined, the depreciation of its assets outpaced that of its liabilities, ultimately leading to an irreparable shortfall.

If these rumors are true, it indicates that the FTX incident involved both types of misappropriation, suggesting that the platform completely ignored the most basic business logic, placing users in unpredictable risk.

Is Misappropriation of Funds by Trading Platforms a Normal Business Practice?

Some argue that using user assets to generate more revenue is a desperate move in a highly competitive market, and that the platform's only mistake was losing money in trading. If the platform could maintain profitability, then all negative consequences would be avoided.

Indeed, this logic reflects the current reality of trading platforms in the cryptocurrency space under intense competition. However, it is still necessary to address whether such misappropriation of funds should be recognized as a normal business activity.

If we set aside the subject of this issue—the trading platforms themselves—and look only at the specific business activities, both types of misappropriation are actually established business models that have long existed.

The first type of misappropriation is quite similar to the lending business of banks or microfinance companies in traditional finance, while the second type corresponds to asset management businesses like funds and VC. So, can we say that the behavior of cryptocurrency trading platforms using user funds for lending or investment is a form of "innovation" aimed at improving capital efficiency?

Clearly, we cannot. Even if we completely disregard regulatory issues, from the most basic business logic perspective, such behavior does not align with the fundamental principles of market transactions.

After all, if the platform profits from misappropriation, the profits belong entirely to the platform, while any losses must be borne by all users. The high "investment" returns occasionally offered by platforms are often just bait used to cover up significant losses, rather than genuine dividends.

In contrast, the business models of banks or fund companies are entirely different. Generally, banks need to pay fixed interest to depositors to compensate for the credit risk they bear, while fund investors, although they share in the losses, also receive the majority of profits through dividends when there are gains.

In simple terms, in these two models, the risks and potential rewards borne by customers are proportional, and users have the right to choose freely based on their preferences, making it a fair market transaction.

On the other hand, the misappropriation by trading platforms operates entirely in a black box. The platform not only enjoys all the profits from misappropriation but also does not have to bear the risk of investment failure. Profits are theirs, while losses are shouldered by users, and it is difficult for them to face regulatory scrutiny and sanctions from major countries. This unequal business opportunity naturally attracts participants lacking moral integrity.

Moreover, this unfair trading has never been transparently disclosed to users at the time of account opening. Therefore, if we directly classify it as fraud, it would not be an exaggeration.

How to Solve the Problem of Misappropriation of User Assets?

Honestly, the issue of misappropriating user assets is not a new problem and is not directly related to cryptocurrency itself. There have been countless painful lessons in traditional finance, and many mature solutions have been explored, which we now collectively refer to as regulation.

1. Compliance Regulation

Although regulatory policies vary slightly from country to country, the overall approach is fundamentally consistent. For example, the "third-party custody" that domestic A-share investors are familiar with involves transferring the custody of assets and funds from trading platforms to third-party banks and securities registration institutions, completely eliminating the ability of brokers to misappropriate user funds. Additionally, there are entry systems for practitioners, severe criminal penalties for misappropriation of funds, regular auditing systems, and so on.

These systems greatly suppress the ability of centralized trading platforms to commit wrongdoing. For domestic brokers, we should rarely hear news of user assets being misappropriated, and there have been virtually no reports of runs on the bank.

2. Trustless Decentralized Trading Platforms

In addition to centralized solutions, another entirely different approach is represented by decentralized trading platforms as a "trustless" solution.

The fundamental purpose of decentralization is to reduce the trust costs of cooperation among social entities. As mentioned in the previous example, traditional regulatory thinking always relies on a larger centralized organization to provide credibility to smaller centralized organizations. However, all of this still relies on trust in a specific organization. But history has shown us that even a powerful centralized institution like the Federal Reserve is not so reliable in the long run. (One can look back at the depreciation rate of the dollar over the past century; compared to a currency that has gone to zero, it can only be said that its decline is slower and more stable.)

Therefore, to fundamentally solve this problem, a completely decentralized technological platform is needed. Based on trust in public chain consensus mechanisms and smart contract code, we can build healthy business logic in an unregulated environment.

For instance, in spot trading on Uniswap, since it does not require custody of user assets, the issue of misappropriation naturally does not arise. All business logic is based on immutable on-chain code and a public chain consensus mechanism with extremely high attack costs.

3. The Grey Area

Of course, the vast majority of cryptocurrency trading platforms currently exist in a grey area between the first two solutions. They lack the regulation corresponding to centralized platforms and do not possess the transparency and verifiability of decentralized platforms, making them hotspots for incidents of misappropriation of user assets.

Strictly speaking, these centralized platforms cannot be considered part of the blockchain industry; they are merely traditional centralized institutions trading cryptocurrency while evading regulation. Their operational philosophy and organizational methods are far removed from the core spirit of cryptocurrency.

Of course, for these centralized institutions in the grey area, the industry has also explored some solutions, including the recently revived interest in Merkle tree proofs of funds.

Due to space limitations, we will not delve into the proof logic of Merkle trees here, and there are still many issues that remain unresolved. For example, this proof can only demonstrate that at a certain point in time, the platform's assets exceed its liabilities, but it cannot confirm whether the assets at that point were temporarily borrowed, nor can it indicate that the platform is free from the second type of misappropriation.

Although improved solutions have entered the theoretical design stage, including the method proposed by Vitalik that uses zero-knowledge proofs for auxiliary verification, these theoretical concepts are still some distance from actual implementation.

In summary, for various trading platforms currently in the grey area, the so-called Merkle tree asset proof can only be seen as a very small subset of traditional auditing mechanisms, and its effectiveness falls far short of expectations. Therefore, Merkle tree asset proofs only create certain obstacles for trading platforms misappropriating user assets but do not fundamentally solve the problem.

Reflections from the FTX Bankruptcy Incident

In conclusion, we summarize some lessons learned from the recent FTX incident.

1. The Core of Financial Products is Risk Management, Not User Experience

The core value of any financial institution lies in the reasonable management of risk, rather than convenience, experience, speed, or other superficial characteristics. Various misguided behaviors have repeatedly appeared in internet finance, and they have been continuously replayed after the so-called "bull market of crypto institutions."

For ordinary investors, if they cannot use regulated compliant centralized trading platforms and are not accustomed to operating decentralized on-chain DeFi protocols, it may be wise to assume guilt when using various centralized platforms in the grey area. At the first sign of trouble, withdraw funds as a precaution, and do not attempt to gamble with your hard-earned money on the personal moral standards of project parties.

2. Trust in Individuals, Organizations, and Authorities is Extremely Unreliable

We often say "Don't trust, verify," but the reality is that people still tend to blindly trust authority.

The history of cryptocurrency development has repeatedly shown us that blind faith in any person or organization is extremely unreliable. The only thing we can trust is a sound system of checks and balances (such as the "invisible hand" of the free market, separation of powers, proof of work, etc.), rather than any authority or individual promising you a bright future (this includes not only the now-defunct FTX but also the likes of Sun and CZ who still wield influence).

Facts have proven, and will continue to prove, that these unchecked centralized entities will only exploit people's trust for their own gain. The only difference may be the specific methods and timing of the exploitation. Therefore, do not simply place your wealth in any unregulated centralized organization; learn to be a "sovereign individual" who can take responsibility for oneself, rather than a perpetual infant needing others to take care of you.