Cruel Reality: The Three Major Contradictions in the Current Airdrop Market

Author: 0xLaoDong

Introduction

The current airdrop market has entered a blatant competition for interests. Project teams tacitly allow data falsification to attract financing while simultaneously conducting large-scale cleaning before airdrops; the "haircut" participants are desperately gambling in the dilemma of "if you don't participate, you definitely won't get anything, but if you do, you might not get anything." This game without a referee exposes the sharpest contradictions in the airdrop market— the tearing between data bubbles and real value, and the opposition between short-term interests and long-term ecology. Lao Dong uses airdrop data from 100 projects over 24 years to reveal the latest trends and hidden rules of airdrops—who is harvesting? Who is being harvested?

I. Conflicts of Project Goals

Core contradiction: Demand for data growth (creating bubbles) vs. controlling token outflow (eliminating bubbles)

"We know that over 80% of addresses are studios, but we must rely on them to complete the ecological cold start." — CTO of a certain L2 protocol

Before the Token Generation Event (TGE), project teams face a dilemma:

Left hand creating bubbles: tacitly allowing studios to batch inflate data, creating on-chain data prosperity (TVL/transaction volume/user count) to attract financing.

Right hand cleaning bubbles: filtering addresses before airdrops and conducting large-scale cleaning.

- Airdrop Type Data Analysis

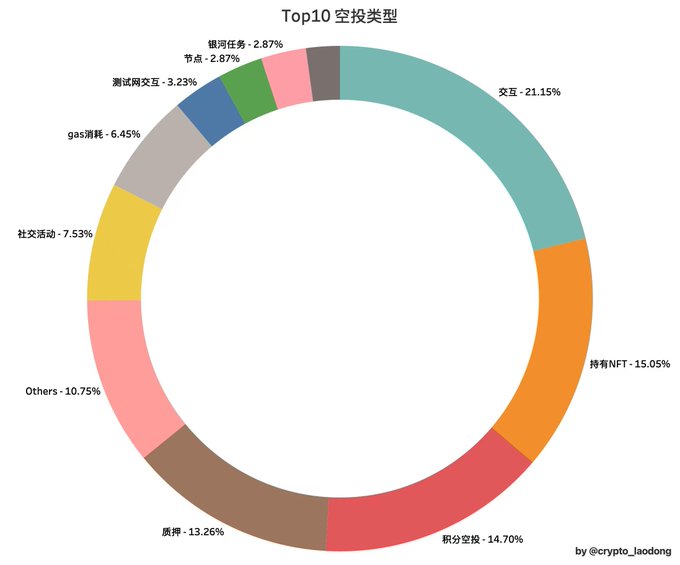

Lao Dong has organized the airdrop rules of 100 projects in 2024 and summarized the proportions of various airdrop types:

Based on project data analysis, interaction, NFT holding, and points airdrops constitute the three main mechanisms in the current market.

Interaction-based airdrops: The primary method of airdrops, mainly concentrated on testnets and mainnets, where project teams use a series of tasks, such as Odyssey events, to increase on-chain interaction data and TVL to attract financing. However, excessive interaction can lead to project teams cleaning addresses. For example, LayerZero had 803,000 addresses deemed as witches, Linea had 40% of addresses deemed as witches, and StarkNet's high-frequency interaction users were marked as bots.

NFT holding-based airdrops: Secondly, NFTs, OATs, etc., often serve as airdrop certificates, most of which require continuous tasks to obtain or are in the form of whitelists where funds are spent to mint. These NFTs are usually tradable on-chain, which also creates potential risks of insider trading, making it difficult to identify, and concentrating chips in controllable hands (e.g., FUEL and Berachain's NFTs, where airdrop distribution ratios are unreasonable).

Points airdrops: Currently a mainstream method, unlike tokens, points are centralized data, which are mutable and opaque, and can be infinitely issued and rules adjusted at will, raising doubts about the fairness of airdrops. For example, ME (points of witch addresses are directly cleared, and exchange ratios vary) and Linea (LXP is an SBT, also another form of points, and tokens may ultimately not receive airdrops). Points airdrops also have serious suspicions of insider trading (EigenLayer's snapshot controversy, Blast's points issuance, and IO's "points shrinkage and stealing points" controversy all have possible insider trading suspicions).

Other airdrop types such as staking, developer rewards, voting, etc., are also different ways for project teams to filter airdrop recipients. However, the opacity of rules, insider trading, and insider information raise doubts about the fairness of airdrops.

- Market Game and Project Team Strategy Choices

The current market is a zero-sum game; the cake is limited, and it is impossible to have it both ways. Project teams cannot simultaneously satisfy their own interests, VCs, users, and exchanges, and must distribute interests and extract value in dynamic games. Faced with the contradictions of airdrop incentives, project teams typically adopt two typical strategies:

Sunshine type: Suitable for small projects or projects with sufficiently generous rewards, such as HYPT, which generally have no filtering, and every address receives rewards. These projects are usually blind grabs, with no clear airdrop rules, making it impossible to determine odds, thus difficult to attract a large number of studios.

Strict filtering type: Suitable for large projects, usually filtering users through points, interaction frequency, rankings, and witch checks, adopting a last-place elimination system. For example, SCR (only those with over 200 points qualify for airdrops), Rune Stones (filtering through holding inscriptions and NFTs), ZKsync and StarkNet (multiple condition filtering), LayerZero (witch reporting system). Although these strategies improve the precision of reward distribution, they also increase uncertainty in participation, putting "haircut" participants at a disadvantage in the rule game.

II. Psychological Contradictions of Participants

Core contradiction: If you don't participate, you definitely won't get anything vs. If you participate, you might not get anything.

Participants also face a dilemma:

If you don't participate, you definitely won't get anything: If you completely refrain from participating in the project, you will inevitably miss out on airdrop rewards. To strive for potential gains, many users have to actively engage in various tasks and activities, investing significant time and resources, further exacerbating market competition and participant anxiety.

If you participate, you might not get anything: Even with significant investment, there is no guarantee of receiving rewards. User input does not correlate with output, as project teams use various means to filter addresses. Complex filtering mechanisms lead many participants to lose airdrop eligibility due to strategic errors or being misidentified as witches.

- Over-competition and Investment Risks

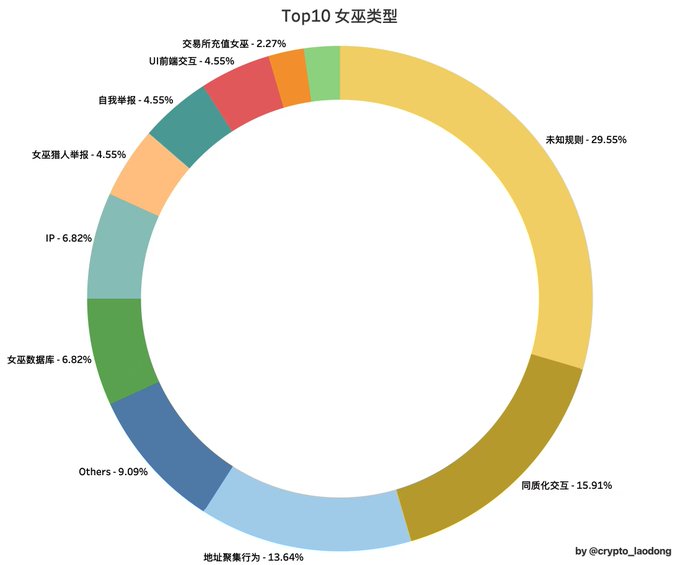

Users, in order to compete for limited rewards, must "produce" a large amount of data and activity. However, the complex and opaque rules and stringent filtering standards make it difficult for participants to predict their actual returns. Among the 100 projects in 2024, 32 explicitly check for witches. Most project teams do not disclose their filtering standards, and the review process is a black box, entirely controlled by the project teams, leaving users like lambs to the slaughter, subject to arbitrary judgments. The following chart analyzes witch types:

The core criteria for project teams to filter witches include:

Homogeneous interactions: A large number of identical operational patterns are the main reason for being deemed witches.

Address clustering behavior: Multiple addresses executing similar operations at the same time and in the same environment are easily recognized and liquidated.

IP, device, front-end interaction: More and more project teams analyze user behavior through front-end data, making simple strategies like changing IPs or devices ineffective.

To survive in this airdrop game, relying solely on funds and luck is far from enough; more refined interaction strategies, stronger technical support, higher anti-detection capabilities, and continuous investment and persistence are also required.

III. Conflicts Between Project Teams and "Haircut" Participants

Core contradiction: Mutual destruction vs. mutual benefit

In the game of airdrop incentives, a "symbiotic" relationship has formed between project teams and "haircut" participants, with their fates closely intertwined:

Mutual benefit: When both parties reach a relatively balanced incentive mechanism, it can attract enough active data while ensuring ecological quality, benefiting both project teams and users.

Mutual destruction: If either party becomes unbalanced, whether due to improper airdrop strategies by project teams or excessive data inflation by "haircut" participants, it will ultimately have a negative impact on the entire ecology, making it difficult for both sides to thrive independently.

Dynamic game:

When participating in airdrop activities, project teams usually set certain thresholds. For example, Linea's POH certification and IP water gate thresholds. When project teams set relatively lenient participation thresholds, "haircut" participants can participate in large numbers, leading to a short-term surge in data. However, once this bubble effect is cleaned by strict filtering mechanisms, the entire ecology may fall into a serious disconnect between data and actual user activity. For instance, after LayerZero announced the completion of snapshots, the number of active addresses on-chain plummeted.

Conversely, when project teams design rules with higher participation thresholds, ensuring that only truly active users who contribute real value can receive rewards. Such high thresholds may prevent a short-term surge in participants but lead to healthy and stable growth of active addresses on-chain, avoiding the creation of data bubbles.

The essence of airdrops is the dynamic game of interests between project teams and users. For "haircut" participants, to steadily secure returns, they must refine strategies, enhance interaction quality, and even build long-term value; for project teams, they should not deliberately pursue financing or listing on major exchanges, and their core task should not be how to manipulate users to create short-term prosperity, but rather how to build a long-term sustainable ecology that truly provides value support.